Trashy trends: challenges of the Bay Area’s free-range waste

By: Daniel McGlynn

Trash near a bridge in Herbert Park in San Pablo, CA, May 1, 2018. This image is from aerial research conducted by Tony Hale and Pete Kauhanen of the San Francisco Estuary Institute. Image credit: SFEI

Trash is one of those issues that seems like it should be pretty easy to solve.

In some regards, trash feels like a very basic environmental health concern. We don’t need complex science to understand what trash is or why it is harmful. The trash problem isn’t really political. We don’t see talking heads on TV saying trash isn’t real, or that it’s a good idea to dump garbage in the Bay or surrounding wetlands.

Nevertheless, despite the basic-ness of the problem, the effort required to fully eradicate trash strewn across the landscape is extremely confounding.

Once trash finds its way into the stormwater runoff system, or in a creek, or ultimately in the Bay, it’s hard — and costly — to get it back to the landfill or recycling center. Instead, it’s more likely to break down, and all of the component parts, usually metals, plastics, and chemicals, then wend their way through the environment.

But there is a lot of work happening on the trash front, and in fact the Bay Area is setting trash trends for the rest of California and beyond when it comes to keeping solid waste out of the stormwater system.

While there are some improvements on the trash front — there’s fewer plastic bags ending up in the Bay thanks to regional ordinances, for example — research shows that lots of trash, particularly plastic, is ending up in the waterways.

To fully keep trash out of the stormwater system requires a multi-tool approach.

Here’s what that looks like.

New clean streets regulations

Since 2009, trying to get a handle on the Bay Area’s free-floating trash has been a focal point of regional water quality regulators. That’s when the first metrics for reducing trash in stormwater runoff were set by the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board in the Municipal Regional Stormwater Permit, kicking off compliance activities by cities and counties around the Bay.

The permitting rules now require municipalities to reduce the trash in stormwater runoff to 100% of the 2009 benchmarks by 2025. This year, cities and counties had to demonstrate that they are at least 90% compliant and on their way to the 100% goal.

“Municipalities who couldn’t meet the goal had to notify us and come up with a plan to meet the 90 percent goal and then the 100 percent goal by 2025,” says Thomas Mumley, the Assistant Executive Officer at the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board. “A majority — about 70 percent — said they will meet the benchmark.”

#regulations

Seeing the trash problem from new angles

Tony Hale from the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) is zooming out on the Bay Area’s trash issues in hopes of better seeing the problem.

One of the hard parts of using aerial images to study and classify trash on the landscape is managing all of the data in a way that makes sense and provides actionable intel.

“This technology is used to come up with a general trashiness level. We can use the data to characterize whether a landscape is clean or not,” says Hale.

“In the course of our surveys, we were able to identify specific trash items, some with great certainty. From 100 feet in the air, we can achieve ½-cm resolution imagery, allowing us to identify coolers, boxes, cans, and sundry items, deposited at the edge of a dry creek bed.”

“In the course of our surveys, we were able to identify specific trash items, some with great certainty. From 100 feet in the air, we can achieve ½-cm resolution imagery, allowing us to identify coolers, boxes, cans, and sundry items, deposited at the edge of a dry creek bed.”

Image from a 2018 flight above a dry Kirker Creek in Pittsburg, CA, showing trash from above. Image credit SFEI

The view from a drone can identify materials that ground-based observations might miss. “Ironically enough,” says Hale, “looking straight down from a considerable distance can often expose more trash than the oblique angle from the nearby edge of a creek. The distant drone, in other words, can reveal trash that might otherwise elude ground-based detection. Also, flying above the landscape can help us to cover much more ground in an hour than a single person or even an entire team can achieve in an entire day.”

#research

Catch and release to filter out the bad stuff

One way that municipalities are addressing the trash-free stormwater regulations is by installing new trash-capture infrastructure.

One tactic is to turn street-level stormwater drains into a network of curbside screening devices. Vendors now build specialized screens that can be installed in stormwater drains and make it possible to filter out trash.

A stormwater trash capture and filtration device designed to work in a distributed manner across a range of street drains. Image credit San Francisco Estuary Partnership

The upside to this distributed solution is that it’s adaptable to different locations and it’s less expensive than retrofitting stormwater drainage systems with new massive trash screening infrastructure. The downside is that the system leaves trash on the landscape, where it can continue to cause a nuisance to neighborhoods.

#systems-thinking

Capturing trash underground

Another method of controlling trash before it hits the Bay sounds a bit sci-fi, but it’s becoming increasingly popular as a way to meet the stormwater requirements.

Cities like San Jose and Oakland have invested millions of dollars into school bus-sized underground systems that separate trash from stormwater.

These systems are complex to install and expensive to maintain (sometimes they need specialized vacuum trucks to clean out the captive debris), but they are a more centralized large-scale solution that can handle filtering runoff from hundreds of acres of landscape.

“It’s like if all of the branches of the stormwater infrastructure tree lead to a trunk, and then you are capturing all trash that flows to the trunk.”

“They can be built at the bottom of a catchment,” says Chris Sommers, the president of the environmental engineering firm EOA and a board member of the California Stormwater Quality Association. “It’s like if all of the branches of the stormwater infrastructure tree lead to a trunk, and then you are capturing all trash that flows to the trunk.”

Cost, space, and plumbing retrofit issues aside, the bus-sized debris catchers are an attractive tool for local agencies trying to meet the trash-free stormwater requirements.

#infrastructure

Netting Installed on Stormwater Outfall – Coyote Creek (San Jose) – Image by EOA, Inc.

Net versus gross

In preparation for the first big storms of the season, Chris Sommers is one of the team of researchers who are attaching big nets to 11 stormwater outlet pipes throughout the Bay Area to monitor the levels of trash in stormwater.

The outlet pipes funnel stormwater before entering the Bay. In a process that is very much like fishing for trash, the goal is to understand the effectiveness of some of the measures outlined above, and to get a handle on what kind of debris is still in the trash stream.

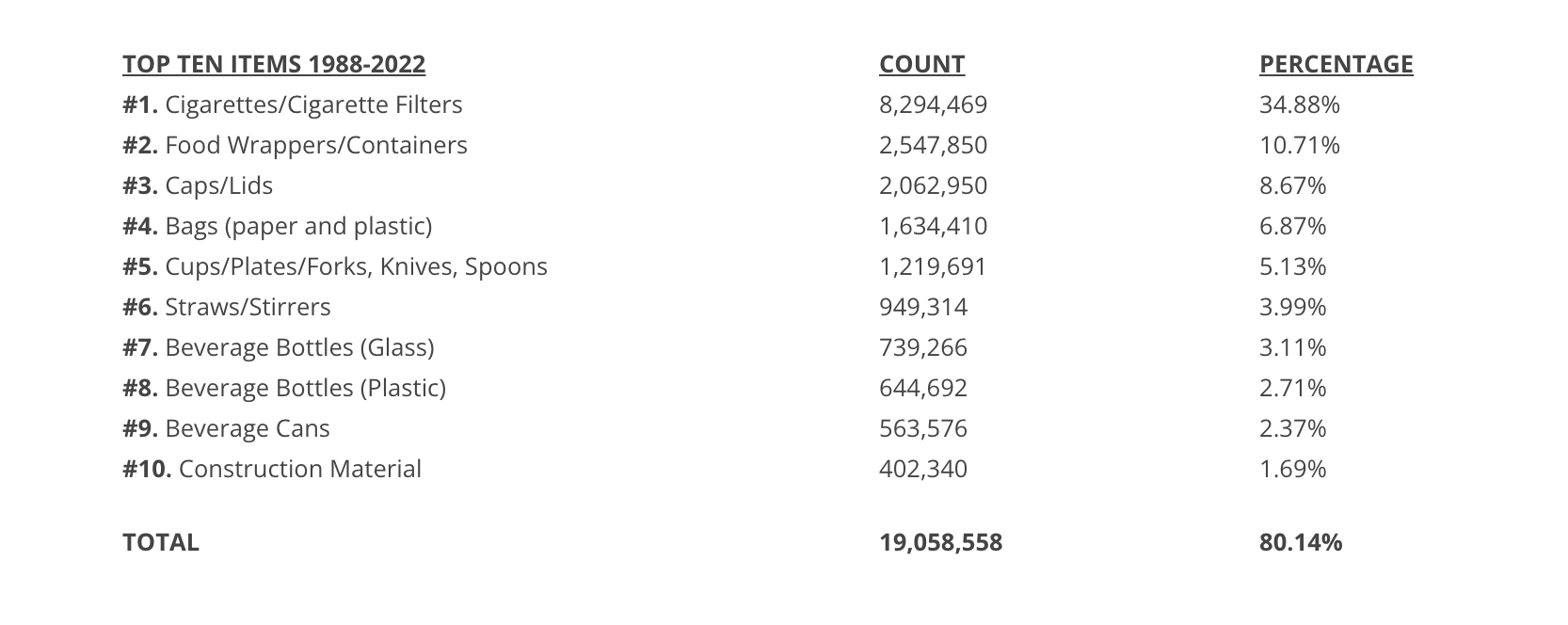

A tally of the top ten items collected from 1988-2022 on California’s beaches by volunteers. Image credit California Coastal Commission.

This winter should provide a good test to see how effective all of the stormwater compliance activities really are, and what still needs to happen to prevent trash from getting into local creeks and the Bay.

#research

Picking up point sources

Moving up the stormwater runoff stream, municipalities are also looking to target point sources of trash generation.

Homeless encampments and illegal dumping are places or issues receiving extra attention and novel interventions (such as providing vouchers to unsheltered individuals for trash that collected/managed in and around encampments, for example) to try and reduce the amount of trash entering the stormwater system in the first place.

Mumley says that for municipalities to achieve the last 10% of the compliance goal will take some on-the-ground-work and require creative solutions, including “getting people to stop trashing our watersheds.”

#policy

Post-trash possibilities

Unlike greenhouse gas emissions or heavy metal deposition, we can see and touch trash. We handle trash on a day-to-day basis. We have systems to dispose of trash, and we attend beach and creek clean-ups. Nevertheless, the problem of trash strewn across the landscape persists because it’s still so easy for so many to just look past.

While the new compliance standards set by the Water Board’s permitting process won’t eliminate trash from the landscape completely, at the very least it will put into place systems and infrastructure to keep trash out of the stormwater system and ultimately, the Bay.

Whether or not we’ll be able to continue to look past trash or come up with reduction strategies before trash gets free in the first place is still an open question.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Daniel McGlynn writes about science, technology and the environment around the Bay Area and beyond. He can be found online at https://www.danielmcglynn.com/.