About the Estuary

What is an estuary? An estuary is defined as where fresh water meets salt water. The San Francisco Estuary is the largest estuary in California, extending from the ridgeline of the Sierra Nevada mountains to the strait of the Golden Gate, including almost 60,000 square miles and nearly 40% of California.

Why does it matter? Water is life. Millions of people, hundreds of communities, and many industries rely on the San Francisco Bay-Delta for fresh water, recreation, agriculture, and more. Additionally, thousands of wildlife species rely on the estuary for habitat. Maintaining a healthy estuary is critical to the communities surrounding it.

Who were the original stewards of the San Francisco Estuary?

For thousands of years, humans have lived and thrived along this rich hydrologic corridor, from the Ohlone, Miwok, Southern Pomo, Wappo, and Patwin peoples who first stewarded this land to the diverse international community that inhabits the region today. There are several distinct Ohlone groups whose homelands collectively extended from north of the Carquinez Strait to Monterey in the south. Many other tribal groups traveled or traded regularly between the Estuary and their home territories and consider the Estuary part of their ancestral lands. The San Francisco Bay Area shoreline was once the site of over 425 shellmounds (Ohlone sacred burial sites), village sites, and ceremonial sites. Today, most Bay and Delta tribal groups do not have federal recognition, which–among other challenges–hinders their ability to protect their sacred sites. See the SFEP Indigenous People’s Acknowledgement for more information about these Indigenous groups and the role they play in managing the Estuary today.

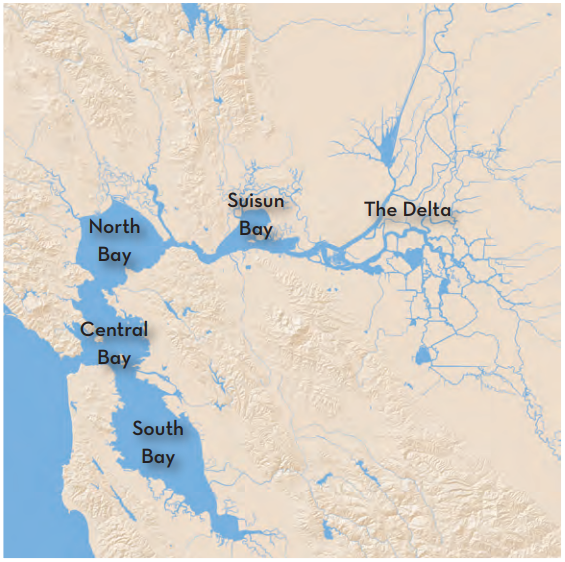

What is the San Francisco Estuary like today? The San Francisco Bay is made up of four smaller bays. The farthest upstream is Suisun Bay, which includes a vast area of marshes. Suisun Bay lies just below the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. Suisun and its neighbor San Pablo Bay, sometimes called the North Bay, are surrounded mostly by rural areas, and are strongly influenced by freshwater outflows from the rivers. The Central Bay is the deepest and saltiest of the four bays. Cities and industries occupy most of its shores. The more shallow South Bay extends south into quiet backwaters surrounded by restored marshes, salt ponds, and office parks and lagoon communities.

Upstream of the Bay, the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is a 1,000 square-mile triangle of diked and drained wetlands. Small remnants of once-extensive tule marshes still fringe the channels that wind between the flat, levee-rimmed farmlands of the Delta’s myriad islands. Before it was diked and drained, the Delta gathered in the fresh waters of the Sacramento, San Joaquin, Mokelumne, and Cosumnes rivers and moved them all downstream through a complex array of channels into the San Francisco Bay. Today, the Delta, with its rich farmland, is the engineered junction of one of the nation’s largest plumbing systems, where much of the available fresh water is diverted to supply California’s population centers and Central Valley Agriculture.

How Healthy Is the Estuary?

- The upper Estuary is in fair to poor condition and getting worse, while the lower Estuary is in better health but jeopardized by climate change.

- Human activities have severely altered the physical processes that create and maintain estuarine habitats.

- The impairment of critical physical processes is intertwined with habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation.

- These losses of physical processes and habitats have reverberated through biological systems, contributing to unproductive food webs, smaller and declining native fish and wildlife populations, and the dominance of invasive species.

The State of the Estuary Report, updated in 2019, provides a comprehensive report for the Estuary.

What Will It Take to Achieve a Healthy Estuary?

A healthy Estuary needs more freshwater flows through the system, more flooding in the right places, more space for habitats and species and connections between those spaces, more sediment moving through watersheds, and less hardscape, among many needs. A healthy Estuary also needs more monitoring of estuarine conditions, as well as funding to learn from and adapt to what works and doesn’t work in restoration and intervention.

The 2022 Estuary Blueprint provides four long-term goals and 25 immediate priorities for achieving a healthier Estuary.