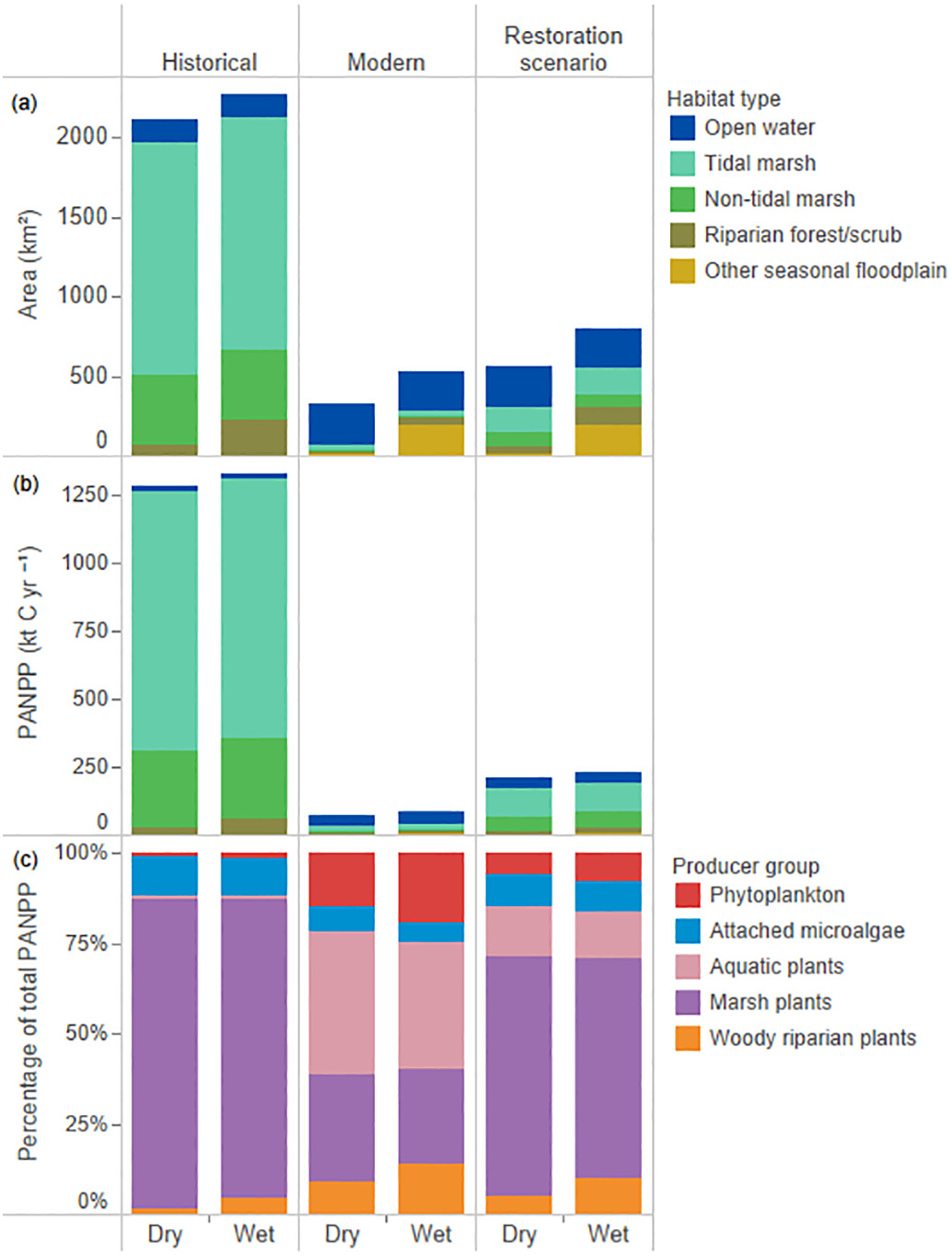

In a new study published in the September 2021 issue of Science of The Total Environment, researchers modeled net primary production of the Delta under historical and contemporary conditions in order to project the potential benefits of restoration. The loss of net primary productivity—the amount of energy available to pass up the food chain—associated with human modification of the Delta since the early 19th century has reduced the energy available to support biodiversity and ecosystem services. Using the San Francisco Estuary Institute’s Historical Ecology Project, which modeled the early Delta based on archival photos, maps, and texts from the early 1800s, researchers estimated the total area for five specific habitat types: open water, tidal marsh, non-tidal marsh, riparian forest/scrub, and seasonal floodplains. The 94% loss of net primary productivity is even greater than the estimated 77% loss of total wetland extent (defined as hydrologically connected habitat), as the Delta lost high-productivity marsh habitat and gained lower-productivity open water habitat.“Not only have we reduced the magnitude of net primary production, but we’ve also transformed the marsh fuel ecosystem into one fueled more by aquatic plants, many of which are non-native, and phytoplankton,” says James Cloern, one of the study’s lead authors, when presenting results at the 2021 Bay-Delta Science Conference. Although habitat restoration could potentially restore an estimated 12% of lost primary production, factors such as invasive species, water management, and climate change mean that these efforts are unlikely to return Delta ecosystem function to its historical state. However, Cloern says the study’s methods could be used to help inform more rigorous wetland restoration programs around the world.

Related Prior Estuary News Stories

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.