When governor Jerry Brown signed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) into law in September 2014, he said that “groundwater management in California is best accomplished locally.” With the first round of plans made available for public comment this year, it appears that, while the state certainly ceded control to local management agencies, those same agencies have prioritized the interests of big agriculture and industry over small farmers and disadvantaged communities. A June 2020 paper from UC Davis published in the international journal Society & Natural Resources, as well as work done by the Fresno nonprofit Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, have shed light on the procedural inequities.

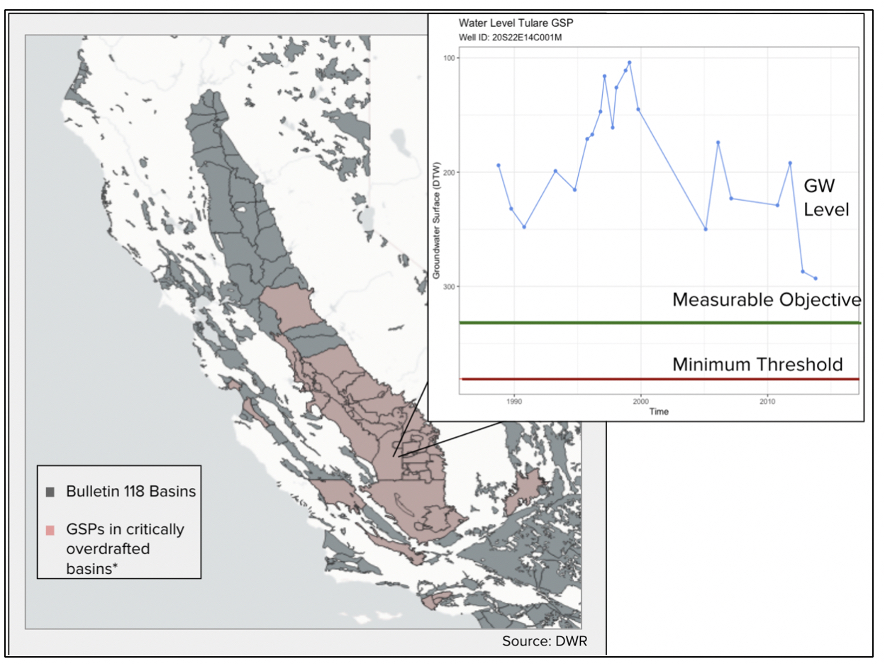

During the 2011-16 drought in California, declining rainfall, snowpack, and availability of surface water led to increased groundwater pumping in farms across the state. This change coincided with many farmers transitioning from row crops to thirsty permanent crops like almonds. A 2016 bulletin published by the California Department of Water Resources noted that 21 groundwater basins in the state were critically overdrafted, up from 11 in 1980.

“Whoever has the access to control how change is made also controls the distribution of harms and goods in society,” said UC Davis doctoral researcher Linda Estelí Méndez Barrientos, a co-author of the journal article, on the July 10 episode of Water Talk, a University of California podcast. In the SGMA process, that access is exemplified by the existing California irrigation districts, along whose lines many of the Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) charged with implementing SGMA in their local basins were formed. Irrigation districts are controlled by farming interests, and GSA boards are dominated by big agriculture. In her research, Méndez Barrientos found that “only 12% of the 260 GSAs have representation from tribal groups, disadvantaged communities, or small farms not affiliated with the irrigation districts.”

Madera County is one example of how GSA agendas don’t always reflect all local interests, as the governor intended. In the last decade, Madera has seen large agricultural operations increase their planting of water-intensive crops like almonds, causing increasing numbers of domestic wells to run dry. When Madeline Harris, policy advocate for Leadership Counsel, made a public comment to one Madera subbasin GSA suggesting incentivizing crop conversion toward something more suitable to Madera’s climate and aquifer condition, the response was not positive. According to Harris, one of the bigger almond farmers on the advisory committee “lashed out and compared that suggestion to Fidel Castro moving Cuba away from tobacco and towards sugar cane. It was hard to move forward meaningful discussion.”

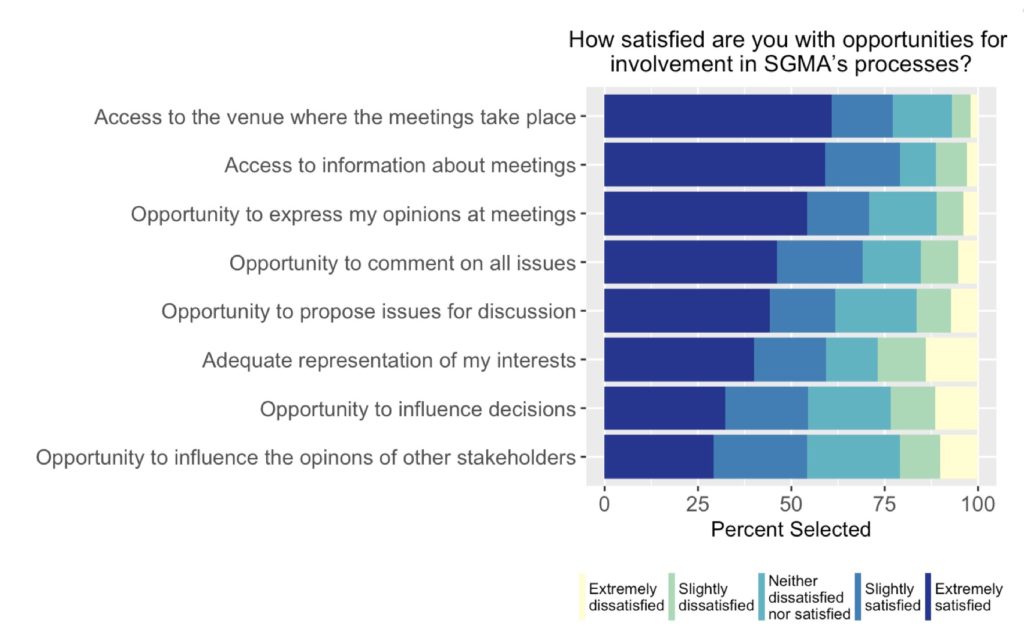

The journal article co-authored by Méndez Barrientos discusses how the “high transaction cost” of participation inhibited many small farmers and disadvantaged communities from participation and proper representation in their respective GSA’s planning process. GSA meetings are typically two hours long and occur on a weekly or biweekly basis. “Let’s say I’m a mother with two kids and I live in the middle of nowhere in the Central Valley,” says Méndez Barrientos. “Going to that meeting is inherently more difficult than if I was a CEO of an enterprise with staff who can go on my behalf.”

Ruth Dahlquist-Willard, an advisor with UC Cooperative Extension and another co-author of the paper, facilitated communication with small farmers, including immigrant and refugee farmers, who struggled to keep pace with SGMA’s technical backdrop. “The payoff is lower,” she says. For farmers who lack the resources to hire experienced staff or consultants to parse the language of a hydrologist or an engineer, “a GSA meeting is not the format that would be helpful for them to understand how SGMA is going to affect their farm.”

The Groundwater Sustainability Plans submitted for many of the critically overdrafted basins in California appear to prioritize big agricultural and industrial interests. While the minimum thresholds for groundwater levels set by many plans don’t endanger the deeper wells of big farming operations, they threaten to leave shallower domestic wells high and dry. “They’re much lower than present-day levels,” says Darcy Bostic, research associate at the Pacific Institute, of some proposed minimum thresholds, “indicating that they will likely continue to withdraw water at a rate that isn’t equal to the rate of planned recharge projects.”

Madeline Harris says that emergency water providers in Madera County are receiving calls from as many as two domestic well owners per week saying that their wells have gone dry. “We’re advocating for a more robust and immediate response in terms of implementing demand-reduction strategies,” she says.

Protecting water for small farmers and disadvantaged communities may require more state intervention, contrary to Jerry Brown’s preference for local control at the time SGMA was signed into law. Méndez Barrientos believes that such intervention is critical if SGMA is to achieve the goals for which it was designed. “In policy, things are path-dependent,” she says. “Once they set a course, it is very difficult to trace that back and correct it.”

Top photo: One of nearly 2600 Asian producers in the San Joaquin Valley, Hmong farmer Chong Ge Xiong grows 40 acres’ worth of bok choy, Daikon radish, sticky rice and other specialty crops. Photo: Kerry Klein, Valley Public Radio

Filling up on Empty, June 2015

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act challenges the diversity of California farms