A fall flight over the Mexican coast where the Colorado River meets the Sea of Cortez offered me a gut-punching, eye-screwing, visual on the results of impaired flow. The semantics of ‘unimpaired’ and ‘impaired’ flow have laced the language of California water management debates since some engineer invented these politically ‘neutral’ terms long ago. The terms refer to our alteration of freshwater flows from snowmelt and runoff by dams and diversions. But whatever the labels, or whichever estuary you’re referring to, keeping these flows from reaching the sea via rivers can starve these aquatic ecosystems of their liquid life force. Whether it’s the vast yellowing salt flats that are all that remain of the mighty marshes of the pre-dam Colorado River delta, or our own estuary at the mouth of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, when we “impair” the flow from the mountains to sea, the result is ecological trauma.

Twenty years ago, the Bay Institute released its own drill-down into this impairment, writing the first ecological history of the vast Central Valley and San Francisco Bay watershed stretching “From the Sierra to the Sea,” as the report is called. A variety of water users, stakeholders, and well-known engineers weighed in on the conclusions, making it more like an early attempt at water community consensus on baseline conditions than an environmental manifesto. In December 2018, the Institute released a 20th anniversary edition –hardbound, and glossy – that includes both a faithful reproduction of the original maps and history, as well as a data-packed, 18-page Afterword summarizing more recent trends.

“For the last twenty years we have been trying to think our way around the central problem of flows,” writes environmental journalist John Hart in his foreword to the new edition. “Maybe, just maybe, if we do a great many things right, we can bring the ecosystem back partway without giving back any meaningful fraction of the water we are taking. On the evidence, this approach has failed.”

The evidence presented in the new edition’s Afterword is a record of continuing collapse. Four more native fish populations (and orcas that feed on Central Valley salmon) have been added to the list of endangered species. Three listed species – winter run Chinook salmon, and longfin and delta smelt – declined by more than 97 percent between the environmentally-proactive late 1990s and 2017. Salinity from ocean tides continues to creep up estuary. Exotic fish are happily ensconced in an altered food web. Extremely high levels of water diversion combined with reduced snowpack, low inputs of sediment from upstream, pollution, and rising sea levels are all exacerbating ecological effects.

“We are in that once-in-a-generation place where we take stock and consider making major changes to how we manage the Estuary ecosystem,” says the Bay Institute’s program director, Gary Bobker, who oversaw production of both the original edition and the 2018 update. The last time, he says, was in the mid-1990s, when Congress and the state adopted major water management reforms, and when big new programs aimed at balancing water use and ecosystem health such as CalFED got off the ground. “That was a decisive time for determining our future, and we’re in that kind of time again.”

Even though the Bay Institute published From the Sierra to the Sea in 1998, its authors contend that it is still the only effort to date to look at the historical ecology of the entire system. Bruce Herbold agrees. “It still sits on my shelf and it still drives the science and management of California’s aquatic resources,” says this former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency biologist who spent decades helping endangered fish up and downstream. “When I started working in this field thirty years ago, one might have expected to see walls, or at least different colored ground, between the Bay, the Delta, and each of the tributary rivers. The divisions still exist, but as witnessed by the State Water Board’s recent controversial plan to regulate streamflows in order to promote better conditions in the Estuary, people are now more likely to view the watershed as connected.” continued

Laser Like Focus on Last 20 Years

Flows Down, Fish Down, Salinity Up, Collapse Closing

For any reviewer, the ups, downs and slices of the bar and pie charts presented in the Afterword of the 2018 From the Sierra to the Sea require time and reading glasses to appreciate. “Reality is complex,” writes Hart. “Yet complexity can also serve as a refuge, sparing us the job of distinguishing between more important things and less important things. The big thing sometimes obscured by the length of the “multiple stressor” list is the first thing on it, the historic and ongoing reduction of flows through the Delta and Bay. The harm done by many of [these stressors] dwindles whenever flows are strong.”

The 18-pages and twenty years (1998-2017) spanned by the Afterword cover changes in inflows, outflows and reverse flows; Central Valley water use; tree crop acreage; native and non-native fish abundance; as well as rising temperatures and water levels due to global warming. More charts and maps fill the pages than words, a mere sampling of which is presented in this article. In some cases, the authors pulled together data from multiple sources to show the interactions between different parts of the estuary and its watershed; in other cases they built on analyses from other well-respected sources and worked to place them in context or extend their scope.

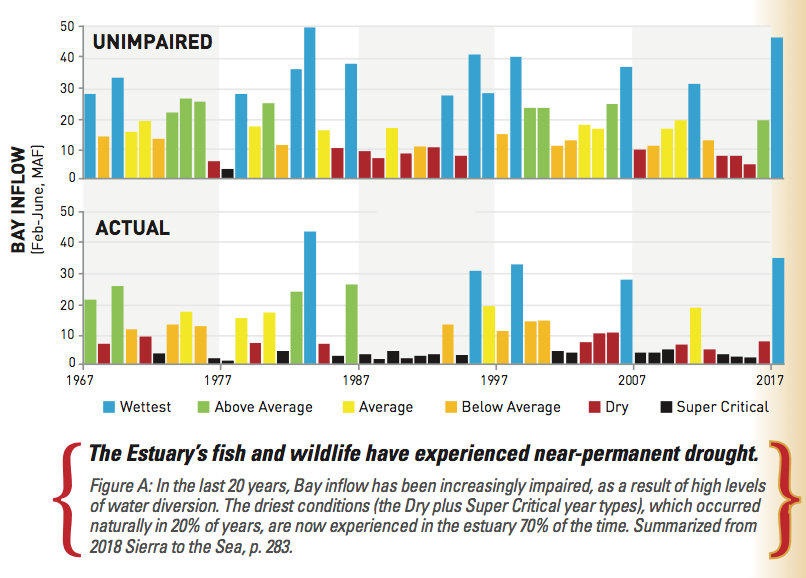

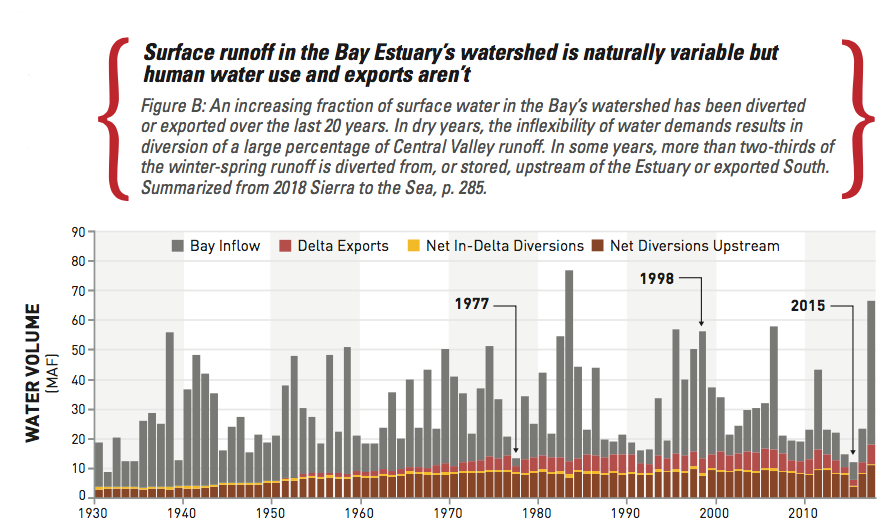

Pulling it all together, the authors come to a variety of conclusions. For one, they counter the argument that major improvements in flow have resulted from the last three decades of policy change. Actual fresh water flowing from the Sierra and Central Valley rivers to the Bay and ocean is now so diminished that the driest Bay inflow conditions, those that would naturally occur 20 percent of the time, now occur 70 percent of the time (see Figures A and B). Without significant flow reinstated to buoy ecosystem processes and habitats, native fish are sure to collapse.

“When populations are near extinction, that’s the time we should strengthen protections, but every time we have a drought, all the rules go out window,” says Bobker, citing changes to Sacramento River temperature requirements in 2014 and 2015 that left salmon eggs with a more than 95 percent mortality rate. “When fish rebound and are viable, and when habitats are large enough to be resilient, that’s when you have more flexibility. So we need to boost growth when conditions are wetter and then design rules for droughts that take into account multi-year impacts – instead of hammering the resource in wet years and dry.”

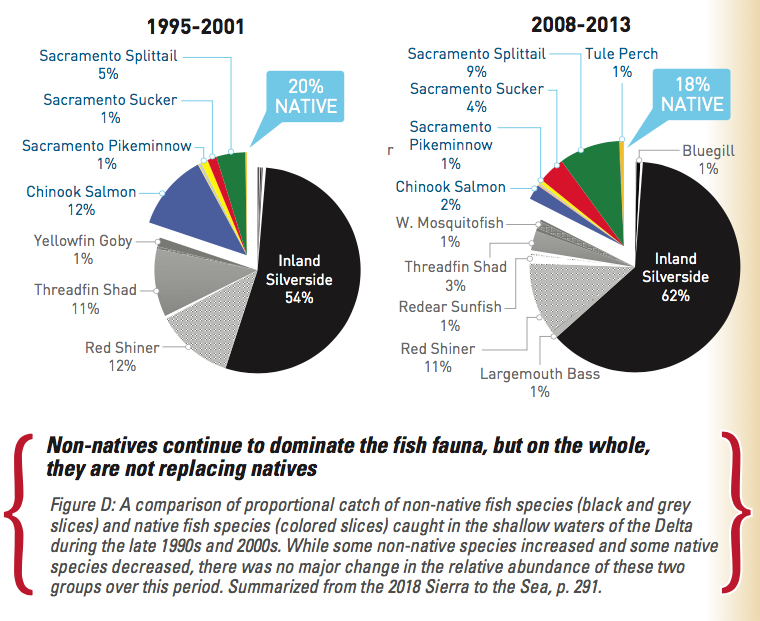

Another conclusion – something of a surprise – was the lack of obvious links between the number of exotic fish species and the health of native fishes (see Fig D). “We all know that the system is now dominated by non-natives but the narrative that this is what has driven the decline of native species over the past two decades doesn’t pan out,” says Jon Rosenfield, the Bay Institute’s lead scientist. “As a group, natives have held their own in the ecosystem since the original report was published.”

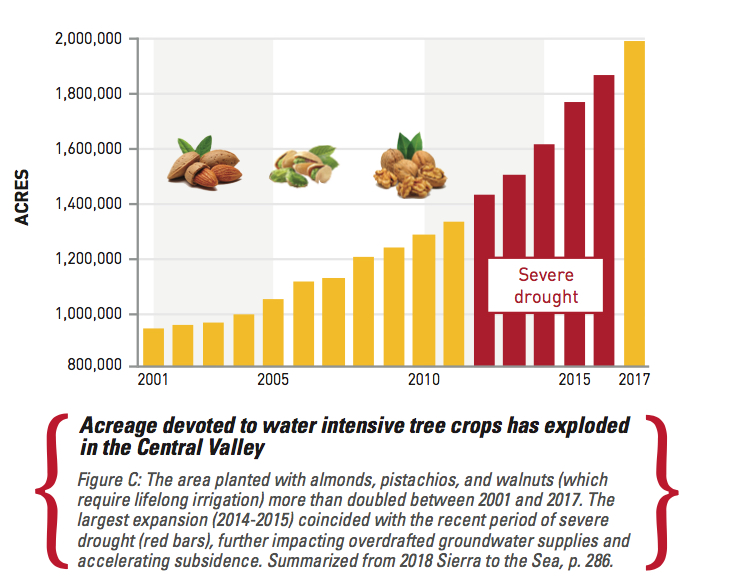

Another conclusion is that despite severe drought and depleted aquifers, the acreage of water intensive tree crops in the Central Valley has exploded (see Fig C). “It makes us realize we should be careful what we wish for,” says Bay Institute report co-author Peter Vorster. Vorster admits that environmentalists have long argued that scarce snowmelt shouldn’t be used on low value crops like alfalfa. According to the Afterword, acreage devoted to high value walnuts, almonds, pistachios doubled between 2001-2017 – increasing by more than million acres – mostly in the groundwater-overdrafted San Joaquin Valley.

Trees “harden” water demand – most orchards have to be irrigated every year and can’t be fallowed in times of drought or flood like field crops. “No one wants to dictate what crops people should grow but we have to make choices about how much acreage to irrigate in order to live within our water budgets,” says Peter Vorster. “Otherwise, our already small water budgets for the ecosystem, and the newly-mandated budgets for groundwater, are at risk. ”

Another surprise emerged as the team cobbled together data from multiple sources spanning 40 years: “The number of days of extreme reverse flows on my spread sheet amazed me,” says Institute scientist Greg Reis. He found that in the record before 1998, reverse flows of -10,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) only occurred in summer on five days. But between 1998-2017, reverse flows of the same or large magnitude occurred on 485 days in summer, or an average of over three weeks per year. “This shifts in heavy exports to the unprotected part of the year is a change that may exacerbate toxic algal blooms and other problems,” add Reis. “Water managers and regulators need to pay attention.”

Other conclusions relate to the changes ahead not behind us – as global warming produces hotter temperatures, more extreme weather including flood events like Oroville, and rising sea levels that will inundate low-lying habitats.

As the Afterword notes, at the time of From the Sierra to the Sea’s publication in 1998, estuary managers recognized global warming as an emerging environmental threat but little imagined its pace and magnitude. What’s clear now, however, is that change will occur more rapidly than previously thought, with serious implications for ecosystems.

Where There’s a Will There’s Way More Fish

A Window for Real Restoration

Even as early as the 1998 edition, the Bay Institute and all those who contributed to the first From the Sierra to the Sea report were recommending landscape scale restoration efforts including support for ecosystem processes such as sediment movement. This early work stimulated a number of further, more detailed, ecological histories and recommendations. The San Francisco Estuary Institute, for example, went on to produce a triumvirate of detailed studies that are now the foundation of Delta conservation management recommendations (Delta Historical Ecology, Delta Transformed, Delta Renewed).

“From the Sierra to the Sea really helped validate the importance of big-picture studies of landscape change, opening the door for more granular analyses like our Delta work,” says the organization’s senior scientist Robin Grossinger.

The new edition’s Afterword restates an obvious conclusion that can now be found in a plethora of scientific and technical documents and management plans, if not political platforms, namely the need to recognize and support processes not just places. And that’s where water comes in again: “What binds together any network of pre-existing or restored habitat reserves in this system is fresh water,” says the Afterword, which mobilizes sediments to create and maintain physical habitats like marshes and beaches; creates low salinity habitat when it mixes with salt water from ocean; transports organisms, nutrients and prey between habitats; cues migratory behavior in salmon and other species; and limits contaminant effects on the ecosystem.

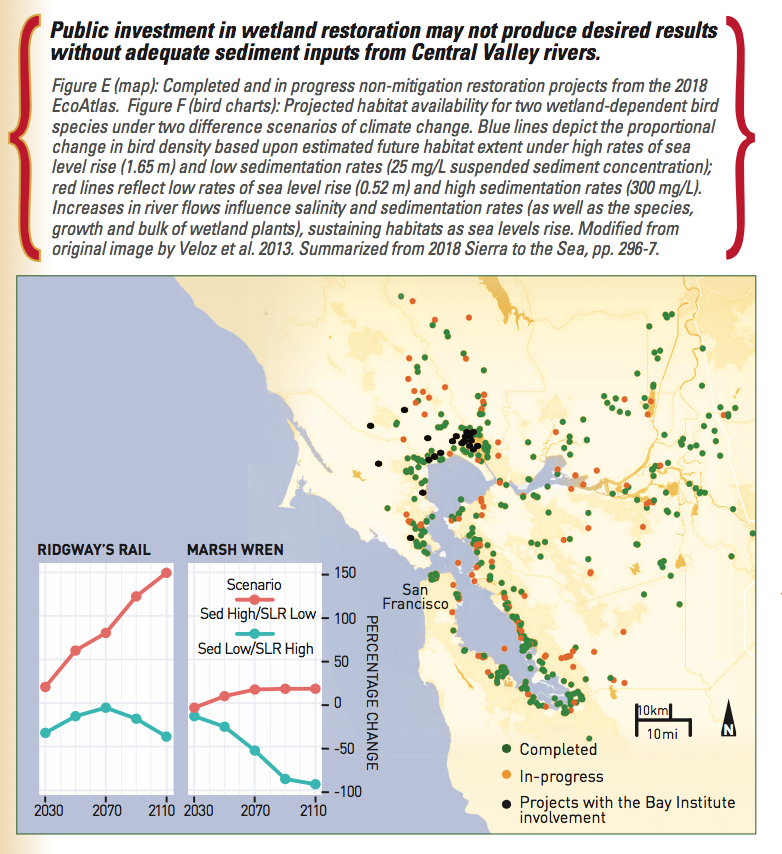

More attention needs to be paid to these ecosystem processes, the Afterword finds, despite the gains made with the addition of hundreds of acres and miles of restoration projects up and downstream in the last 20 years – from gravel augmentation in tributaries to levee setbacks and floodplain expansion in Central Valley rivers to wetland and creek restoration around the Bay. These include one of the largest and most ambitious projects championed by the Bay Institute – restoring fresh water and salmon to 150 miles of the San Joaquin River, once dry down to the sandy river bottom due to “impaired” flows.

Landscape managers are now concerned that all this work to grow species and habitats will be undone, or produce different outcomes, as air and water temperatures rise and the ocean advances upstream. Recent fires, floods and drought have already galvanized the public to consider more ways to support natural resilience. The political will to really reshape land use practices, however, remains weak, as have commitments of more flows to fish.

“Governor Schwarzenegger’s Delta Vision task force did a great job of highlighting all these emerging threats and how we needed to reconnect and rehabilitate parts of the estuary. Then we got sidetracked. Governor Brown then got fixated on delta conveyance rather than larger water management changes and California lost a precious decade when we could have been addressing the root causes of the Estuary’s decline,” says Bobker.

“Now is the time to do the rest of the restoration, to add the critical element of water, if we want our investments to pay off,” says Rosenfield.

“Building resilience doesn’t require us to stop all human use of California’s water, just to do a better job of sharing it,” says Bobker.

2018 From the Sierra to the Sea, The Bay Institute

Watershed – The Movie (Colorado River story)

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.