DOWNLOAD the December 2016 Issue PDF

DOWNLOAD the December 2016 Issue PDF

By Kathleen M. Wong

Off a bustling Delta highway, next door to a branch of the California Aqueduct, sprawls a tidy collection of shipping containers, humming pumps, and cylindrical tanks. Paved in cracked asphalt and encircled by chain link fencing, it resembles any number of light industrial sites at the margins of many communities.

In fact, this resolutely artificial site is devoted to preserving a disappearing piece of natural California: the Delta smelt.

“Our fish are a refuge population,” says Tien-Chieh Hung. Director of the UC Davis Fish Conservation and Culture Laboratory, Hung oversees this one-acre facility on the outskirts of the tiny town of Byron.

Opened in 1996, the facility was initially charged with producing Delta smelt for experiments. It took a decade for researchers to replicate the fish’s life cycle in captivity. “We joke that it dies if you look at it the wrong way,” Hung says.

Now, with smelt production down pat—“we might have more Delta smelt here than in the wild,” says Hung—the facility is shifting directions. That’s why Hung has recently divided the facility in half; fish on one side are destined for science, while those on the other are what Hung calls “a living gene bank.”

Another way to think about cultivated smelt is as an insurance policy. Should the unthinkable occur, and Delta smelt are no longer viable in the estuary, this refuge population could someday be reintroduced to the wild. In that way, they would be like finny versions of the California condor, maintained solely in captivity for years until conditions were right to release them again.

Playing God

Maintained by humans outside of its natural habitat for conservation, Hypomesus transpacificus could be the first of a number of Delta species on artificial life support.

In this December’s issue of San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, three eminent scientists report that “it is increasingly irresponsible to focus entirely on a policy of in situ conservation through habitat protection and restoration.” Conditions in the Delta are so dire, write Michael Healey of the University of British Columbia, Michael Dettinger of the U.S. Geological Survey, and Richard Norgaard of the University of California, Berkeley, that “alternatives to conservation in place” should be explored for the Delta’s most endangered native species. These so-called “orphan species” include winter-run Chinook salmon, green sturgeon, Lange’s metalmark butterfly, and the salt marsh harvest mouse.

“The longer the delay, the harder the decisions, and the less likely they are to produce positive results” the authors warn.

“There’s still this big desire to maintain species in the location that they currently exist. I’m all in favor of that, but it’s time to start asking the ‘what if’ questions. What if we can’t do that? What’s Plan B?” asks author and salmon expert Healey.

The “alternatives” they propose run the gamut from tame to radical. Some are extensions of accepted practices conducted for conservation purposes. Others require a level of human intervention that is nothing short of heroic. But all seem destined to become a hallmark of conservation biology in the Anthropocene.

“The ecosystems of the Delta are classic examples of a habitat totally dominated by humans. We’re responsible for making it work, or not,” says Peter Moyle, emeritus professor with UC Davis. “The only way it’s going to be good for native fish is if we want to make it so. We can play God.”

A polder for Delta smelt

With a refuge population near Byron, and a second backup population at the Livingston Stone Hatchery below Shasta Dam, Delta smelt might seem secure for the time being.

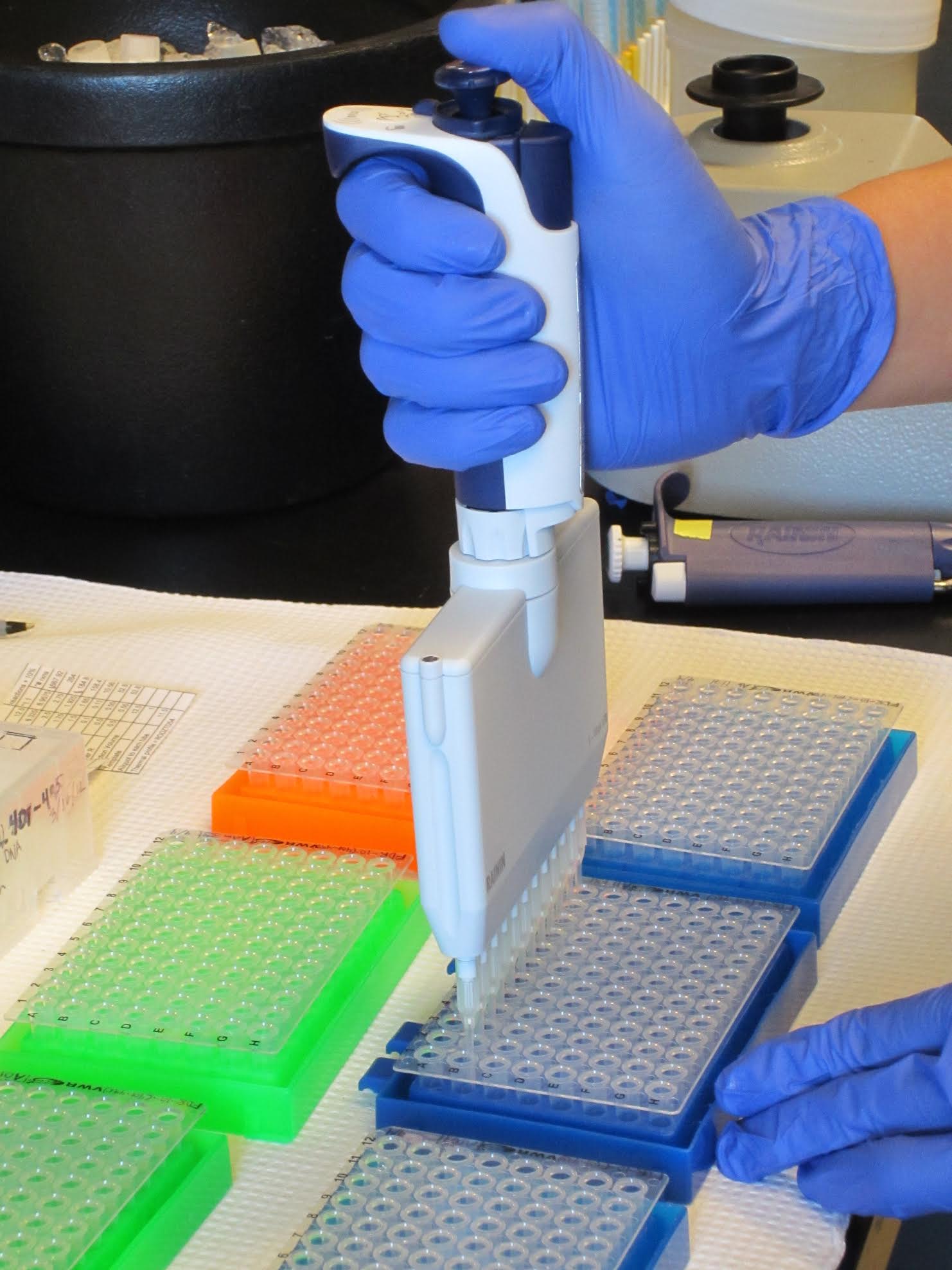

But in a hatchery, smelt get domesticated fast. Its one-year life cycle leads to brothers mating with sisters. To keep the small population at the fish culture diverse, scientists genotype all candidate parents, breed many two-year-old fish, and catch up to 100 wild smelt per year for the program. Without a source of wild genes, says Moyle, “you wind up with a very domesticated population unless you quickly figure out how to reintroduce them into the wild, at least experimentally.”

To maintain a wild smelt population, one option is relocating cultivated fish to a flooded Delta island, or polder. Isolated from predators, awash in food, this refuge population would serve as insurance should wild populations go extinct.

More interventionist yet would be intensive, landscape-scale habitat management. “We’ve failed trying to manage the entire Delta for smelt. So we want to concentrate our efforts on making this arc of habitat from Yolo to Suisun Marsh a more natural estuary, but not try to do that for whole Delta,” Moyle says. With a number of restoration projects already underway in the so-called North Delta Arc, this option could aid other native fishes such as tule perch, lampreys, and sturgeon.

Freezing living things to revive them at a later date can stop time for species at risk. Whether its cheetah embryos at the San Diego Zoo or skin cells scraped from Delta Smelt in Byron, cryopreservation is already being explored worldwide…

California salmon…in Canada?

While ecosystem conditions threaten smelt, climate change poses the primary problem for far more species. As rain and snowpack decline, plants such as oaks and redwoods might see their ranges contract. A hotter climate will exacerbate drought conditions. And as sea levels rise wetland species like the salt marsh harvest mouse could get inundated.

Winter-run Chinook is one species considered at risk from a hotter climate. Spawning in summer when water temperatures are at their warmest, this salmon requires cool water from Shasta Dam for its young to survive. “Another five- to seven-year drought and there will be no cool water pool in Shasta Reservoir,” says salmon expert Healey. “They are really in a tenuous position.”

To preserve this genetically distinct salmon, Healey proposed a case of assisted migration: relocating the fish all the way to the Arctic Circle. In virgin watersheds newly exposed by receding ice, it could access plenty of cold water. Certainly people have had plenty of experience moving fishes to new areas; witness the longstanding programs to stock Sierra Nevada lakes with trout.

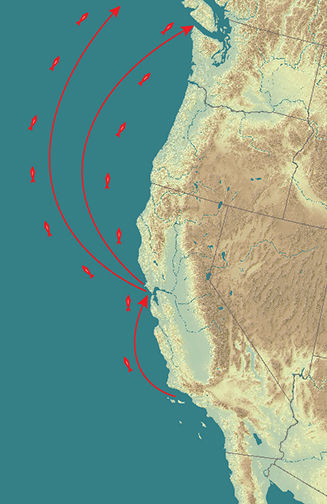

Healey argues the difference between assisted and natural migration is merely a matter of degree. “We’re really talking about resisting a process that’s going to happen anyway,” he says. The Pacific is expected to serve as a corridor for anadromous species such as salmon and sturgeon to colonize cooler northern climes.

The time to act, the report scientists say, is now. “You need to generate the willingness on the part of the policymakers and all the people involved. Plus you need to develop the scientific foundation to carry it through. So if you wait until the last lonesome individual is teetering on the brink, it’s too late,” Healey says.

Uncharted territory

Not so fast, argue other scientists. “Alternative conservation” measures are phenomenally costly, raise a raft of ethical and political questions, and could even sap the public’s will to make the Delta ecologically healthy again.

One issue with assisted migration is that it upends the idea of species being integrally connected to habitat. The Endangered Species Act defines each species in part by its “unusual or unique ecological setting.” In other words, a species is inseparable from its habitat.

In the case of winter-run Chinook, fish moved to the arctic will be on a completely different evolutionary trajectory than their Delta relatives, and would no longer be considered protected under the current language of the ESA.

“What those objections ignore of course is that these habitats are changing dramatically as a result of climate change, and species already in the Arctic might not be able to survive that transition,” Healey says.

Environmental shifts will happen too fast for many species to migrate to areas with more comfortable conditions, and in many cases highways, farms, and cities may block natural migration corridors. To prevent extinctions, scientists have proposed moving species to new habitats they won’t be able to reach on their own….

An ethical conundrum

Salmon and smelt are hardly the only organisms that could require intensive human intervention to survive. With a finite amount of political will and funding to devote to conservation, society will have to prioritize which to aid, and which to leave to their own devices.

“We probably won’t be able to preserve every species unique to the Delta by any of these techniques. So there’s going to have to be some triage. Which ones will we invest in and which ones won’t we? These are going to be really hard discussions,” Healey acknowledges.

“It goes right to the heart of what conservation is all about. Is it most important to save every species? Preserve the functioning of natural ecosystems? What is our objective?” says John Wiens, former chief scientist of The Nature Conservancy.

“We need to stand back and have some thoughtful discussion about what we’re really trying to achieve in conservation and management of these populations. Because if we don’t do that, then we’re going to get caught by the speed of change and find we haven’t really used our resources wisely and achieved as much as we could,” Wiens says.

The people involved will have to include not just politicians and scientists but also bioethicists, legal policy experts, and stakeholders such as fishermen, aboriginal groups, and regional residents.

The growing body of scientific literature on climate change adaptation indicates that the “alt conservation” dialogue has at least begun. Bioethics and legal experts will need to be involved, in addition to stakeholders such as governments and aboriginal groups.

For example, it might be more critical to intervene on behalf of restricted endemics such as the Delta smelt, Lange’s metalmark butterfly, and the salt marsh harvest mouse, because if they disappear from their Delta range, they will be gone forever.

But already some conservationists contend that preserving individual species is irrelevant due to the rapid pace of climate change. They point to the development of novel ecosystems, assemblages of species that have never been seen before. In such an environment, choosing species for their hardiness or to serve a function such as food delivery or water filtration could be the way to go.

People are already engineering habitats to withstand climate change around San Francisco Bay. For example, plant species chosen for wetland and creek restoration projects are now being selected for their tolerance to hotter, drier conditions.

“We may not have the habitats that contain the species they used to. But we can provide a more or less natural setting for natural ecosystem processes to exist. New species will come in through introductions or as they move about in response to climate change. If you’ve got the places for them, and can manage the habitat, you are maintaining a sense of naturalness even though those species weren’t necessarily there 50 years ago,” Wiens says.

Many organisms can’t evolve fast enough to survive our rapidly changing climate. Scientists are already trying to help corals become more heat-tolerant. Assisted evolution, with humans lending a helping hand to genes that confer resistance to, say, drier or hotter climes, may be the next level in the survival game…

Remaining traditional options

While discussion of alternatives is happening, it’s safe to say no one is ready to abandon the idea of conservation in place.

“It’s way too early to throw in the towel for conserving species in their native range,” argues Steve Lindley of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

Regarding Sacramento winter-run Chinook, “It is absolutely crucial to conserve what we have left, especially populations at the southern end of their range in the Central Valley. They presumably have the best genes for dealing with hot, dry conditions. They could help more northerly populations deal with climate change.”

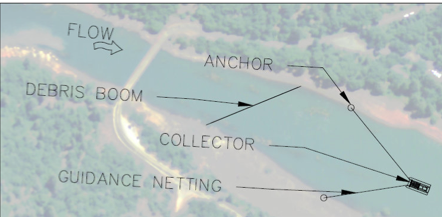

Lindley cites plans to trap winter-run Chinook at Keswick Dam near Redding and truck them behind Shasta Dam as early as next summer. This would enable adults to access the snow-cooled tributaries where they originally spawned. Juveniles would be trapped in floating surface collectors being engineered now, and transported below the dam.

“Hydrologic conditions there are still perfectly suitable for Chinook, and those streams may still be cold even under conditions of future climate change,” Lindley says.

Legislative and policy definitions also will need to change to consider the realities of our shifting world. That’s already happening at NOAA. “There is new documentation to incorporate climate science into management, as well as a national climate science strategy and western science action plan to guide us,” Lindley says.

A dangerous path

Some view alternatives to conservation in place as a threat to the ultimate goal of the ESA and other management efforts: restoring the Delta to a functioning, healthy ecosystem.

“People treat these alternatives as a solution as opposed to a temporary stopgap. But the alternatives just make the symptoms go away and don’t address the underlying problem, they’re just a Band-Aid,” says conservation biologist Jonathan Rosenfield of The Bay Institute.

He admits the dire straits of the Delta now demand exceptional measures—at least in the short term. “We need to be prepared to Noah’s ark these fish for however long it’s going to take to restore their ecosystem,” he says.

But scientists must take care when presenting more alternatives to conservation in place before decision makers. “We have to deliver that full message every time: that the metaphorical flood subsides when we actually restore the ecosystem,” he says.

“There are people who will think, once we’ve got them in the hatchery, or rearing in some offsite habitat, then we don’t need to protect the Delta anymore.”

The reality is, the problems of the Delta will not disappear if its smelt go extinct. Over the past 20,000 years, this delicate fish has survived major changes in climate, torrential floods, and even massive volcanic eruptions. Now the waters it swims in are becoming a toxic soup of algal blooms, mercury and pesticides that is growing hotter all the time. That can’t possibly be good for the 25 million people who rely on the Delta for their water supply.

“We have the data and the understanding and the management principles by which we can move the Delta to health. We just need the political will to do that,” Rosenfield says.

In the meantime, thousands of Delta smelt in Byron will continue to swim in circles around their darkened tanks, oblivious to the furor over their fate.

LINKS

Shasta Dam Fish Passage Evaluation

State of Bay-Delta Science Articles July, October, December 2016