by Joe Eaton

According to the Biblical book of Leviticus, the ancient Israelites designated a goat to bear the weight of their sins. Nowadays, the scapegoat is not required to be a goat. When it comes to assessing blame for the worsening California drought, a scapefish will suffice. Some media outlets, notably the Wall Street Journal in a recent op-ed piece, point to the hapless Delta smelt as a culprit in the state’s water crisis, as well as a prime example of the iniquities of the federal Endangered Species Act.

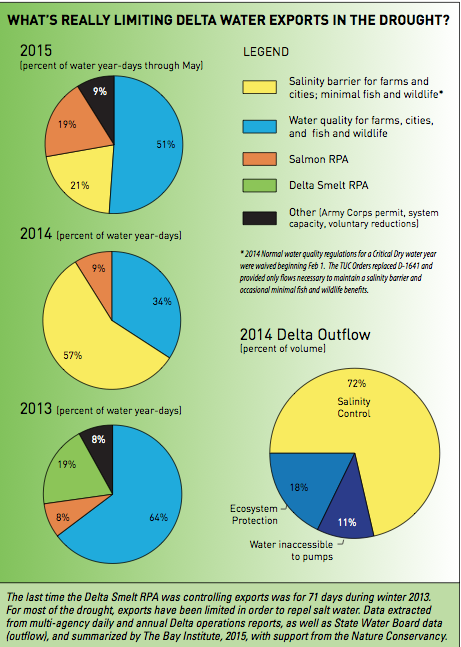

As is so often the case, though, it’s not that simple. Day-by-day analysis of water exports from the Delta by Jon Rosenfield and Greg Reis of The Bay Institute shows that smelt protection has had very little to do with water export restrictions during the drought. The bottom line is that water allocations have been cut because of record-low snowpack and reduced runoff. When diversions by the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project have been further curtailed over the last three dry years, it’s usually because water quality regulations that safeguard water for cities and farms against excessive salinity also limit exports in order to ensure that the projects can pump fresh water to urban and agricultural customers. Protection of endangered anadromous fish like salmon and steelhead has played a minor role, but delta smelt regulations have not governed exports since early in 2013. As for the ESA, supporters argue that it’s far from the draconic and inflexible law caricatured by its critics. Its real shortcomings are insufficient commitment to the recovery of imperiled species and a chronic lack of funding for implementation.

As is so often the case, though, it’s not that simple. Day-by-day analysis of water exports from the Delta by Jon Rosenfield and Greg Reis of The Bay Institute shows that smelt protection has had very little to do with water export restrictions during the drought. The bottom line is that water allocations have been cut because of record-low snowpack and reduced runoff. When diversions by the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project have been further curtailed over the last three dry years, it’s usually because water quality regulations that safeguard water for cities and farms against excessive salinity also limit exports in order to ensure that the projects can pump fresh water to urban and agricultural customers. Protection of endangered anadromous fish like salmon and steelhead has played a minor role, but delta smelt regulations have not governed exports since early in 2013. As for the ESA, supporters argue that it’s far from the draconic and inflexible law caricatured by its critics. Its real shortcomings are insufficient commitment to the recovery of imperiled species and a chronic lack of funding for implementation.

Here’s a taste of the Wall Street Journal piece: “To protect smelt from water pumps, government regulators have flushed 1.4 trillion gallons of water into the San Francisco Bay since 2008….Parched Californians may soon wonder when it’s their turn for such concern.” Similar interpretations have surfaced on Fox News and elsewhere. But Rosenfield and other knowledgeable water-watchers say these viewpoints are misinformed at best, disingenuous at worst. Delta water is not being wasted by being flushed out to sea: it’s working hard to serve multiple purposes for Californians, urban and rural alike.

“Clean Water Act protections have controlled Delta exports on most days by far over the last three years,” says Rosenfield. That was true even after the State Water Resources Control Board weakened or eliminated water quality protections for fish and wildlife in separate actions in 2014 and 2015. The intent of the Water Board regulations is to manage salinity in the Delta by tweaking freshwater flow rates, in the interest of agricultural irrigators and urban customers. From 2013 through March of this year, water quality regulations have governed exports on 75 percent of all days, salmon protection on 11 percent, smelt protection on a mere 8 percent. (Army Corps of Engineers permits, voluntary reductions, and system capacity accounted for the remaining 6 percent.) On no day in 2014 or 2015 were ESA smelt protections triggered.

As Rosenfield explains it, the regulatory mechanism for constraining water exports that might impact sensitive species begins with an interagency consultation under Section 7 of  the ESA. The water agencies — the federal Bureau of Reclamation and the California Department of Water Resources — are required to present their operational plans for review by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service. The fish and wildlife agencies then issue species- specific Biological Opinions. “If the operation plans would cause or increase the jeopardy of extinction, the wildlife agencies need to provide Reasonable and Prudent Alternatives (RPAs) to the plan,” he says. Separate but overlap- ping RPAs govern the delta smelt, under FWS jurisdiction, and salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, and orcas, under NMFS. On any given day, one of the RPAs may trigger a reduction in ex- ports. They operate along with, and as a minor adjunct to, the Clean Water Act regulation. Because of the prolonged and severe drought conditions, the water quality protections are triggered more frequently. Rosenfield says The Bay Institute’s analysis shows that the smelt RPA has had no effect for most of the current drought. “The salmon RPA limits exports on some days,” he adds. “And even when the RPAs are limiting exports, they don’t get shut off; they just get turned down.”

the ESA. The water agencies — the federal Bureau of Reclamation and the California Department of Water Resources — are required to present their operational plans for review by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service. The fish and wildlife agencies then issue species- specific Biological Opinions. “If the operation plans would cause or increase the jeopardy of extinction, the wildlife agencies need to provide Reasonable and Prudent Alternatives (RPAs) to the plan,” he says. Separate but overlap- ping RPAs govern the delta smelt, under FWS jurisdiction, and salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, and orcas, under NMFS. On any given day, one of the RPAs may trigger a reduction in ex- ports. They operate along with, and as a minor adjunct to, the Clean Water Act regulation. Because of the prolonged and severe drought conditions, the water quality protections are triggered more frequently. Rosenfield says The Bay Institute’s analysis shows that the smelt RPA has had no effect for most of the current drought. “The salmon RPA limits exports on some days,” he adds. “And even when the RPAs are limiting exports, they don’t get shut off; they just get turned down.”

Rosenfield and Reis mined their data from public annual and daily reports by the multiagency Delta Operations for Salmonids and Sturgeon group of water and wildlife agencies documenting water project (SWP and CVP) exports; in-Delta diversions are not included. He notes that some interpolation was needed: “There are times of year, mainly summer and fall, when no one provides updates on what’s controlling exports. This preliminary analysis requires an educated guess. But that wouldn’t change the story in terms of the proportion of days when the RPAs are controlling.”

Others have stressed the state’s multiple goals in regulating Delta exports. “Delta outflow is also essential to maintain water quality for farmers and cities in the Delta, and ultimately for the CVP and SWP itself: freshwater flowing out of Delta pushes against the tides bringing saltwater upstream, creating a barrier that enables the CVP and SWP to pump fresh water instead of salt water,” writes Doug Obegi of the National Resources Defense Council in his blog. In fact, the Water Board’s analysis of 2014 Delta outflows shows that 72 percent of the water that was not exported last year was needed simply to control salinity intrusion into the Delta.

Beyond smelt and salmon, the Endangered Species Act is the real target of media critics like Finley and their political allies. “The ESA is doing what we asked it to do, preventing species from going extinct,” Rosen- field notes. “Although it’s one of the best-written pieces of legislation we have, it could be better in making sure listed species recover. There’s no legal enforcement of recovery at all.” He adds that if the Clean Water Act and other environmental legislation had been properly enforced, “the ESA would be far less relevant.”

Rather than revising the federal act, Obegi advocates giving wildlife agencies adequate resources to implement it. “There’s a huge backlog of species awaiting listing, including California’s longfin smelt,” for which protection was determined to be warranted but precluded by lack of funds. Recovery plans for a number of non-pelagic species needs to be updated. Obegi also says more grants for habitat restoration and even simple devices like fish screens could reduce the conflict between water supply and environ- mental protection.

Mark Rockwell’s Endangered Species Coalition has its plate full defending the ESA from Congressional attempts to weaken it (at press time, eight such bills were pending in the US Senate). The problem with reauthorizing the act, he says, is that it can’t be done selectively: “When you open up the law, you open it up for everything.” If a changed political climate allowed constructive revision, Rockwell would like to see a stronger emphasis on species recovery in Section 10 of the Act, which governs Habitat Conservation Plans, and a way of insulating the critical habitat designation process from political arm-twisting.

Rockwell and Obegi agree that major changes in the way California uses water can defuse the fish-versus-farms controversy. That would include realistic pricing for irrigators, meaningful penalties for residential water wasters, tackling the antiquated and baroque water rights system, and conservation strategies like recycling, conjunctive use, and groundwater storage enhancement. Rockwell’s group has identified 55 actions the state can take to ride out the drought. “We don’t use water efficiently everywhere in this state,” he sums up. “It’s time we learned how to do that. The drought creates an opportunity for a come-to-Jesus meeting on this.” Finally, we may be able to move beyond scapefishing.

CONTACT: Doug Obegi; Mark Rockwell; Jon Rosenfield

NEXT STORY: Beyond the Blubber