In June, Mountain View’s Permanente Creek is barely a trickle. Culverts burp water into a concrete channel abutted by schools, houses, and ballparks. A pair of mallards splash through the water, not even up to their ankles. After a dry winter, it’s hard to look at these conditions and imagine that gurgle of water rising up over its concrete banks to flood the city, which might explain part of the decade-long push and pull between some residents and flood managers over the adjacent McKelvey Park.

Along Miramonte Avenue, and almost 20 feet below it, sit a couple of baseball fields, both in use on a Saturday afternoon. Parents are in attendance behind home plate, but rather than sitting behind a chainlink backstop at field level, they look down from bleachers at the top of vertical concrete walls. McKelvey Park’s curious design reveals its double use: a 0.7-acre, 18-foot deep basin designed to protect Mountain View from Permanente’s next major 50- to 100-year flood.

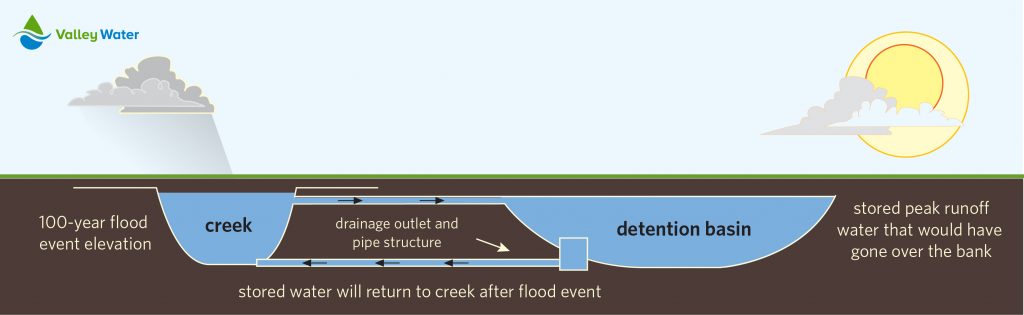

Flood detention basins like the one at McKelvey Park, according to Afshin Rouhani, an engineering manager in water resources with the Santa Clara Valley Water District, can help solve the problem of urban flooding. Many South Bay creeks like Permanente have been locked into a concrete channel to protect adjacent developments, but in extreme flood events, they can overflow their walls and spill out across the densely populated floodplain. “One solution is to build the channel bigger,” suggests Rouhani. “Another is to take the peak off.” In other words, when Permanente floods, peak storm flows are diverted into the McKelvey Park basin. As the basin fills up, the creek level maintains, then drops, and when the flood recedes, the water held in the basin is returned to the channel.

Projects like McKelvey Park are feats of engineering, and come with a commensurate investment of time and capital. Valley Water began planning the project in 2003 and construction was only just completed last year. The detention basin forms a part of a larger flood-protection program along the creek’s path from the mountains to the Bay.

Despite the project’s dual function of flood protection for the city and sports complex, the project was not met with universal enthusiasm from the community. Public comments from various Mountain View Voice articles about the McKelvey Park construction include complaints about the costs and inconveniences associated with the construction. Other complaints seem to show a lack of concern for any potential future floods: “Ten million [dollars] to plan for a storm that has a 1% chance of happening each year?” And “Permanente Creek has not flooded since…1959.”

Leaving aside the fact that, according to Valley Water, Permanente Creek has experienced major flooding four times since 1959, the scientific understanding of extreme climate events in California in recent years has changed. Scott Dusterhoff, lead geomorphologist with the San Francisco Estuary Institute, suggests that, even if summer is getting longer, hotter, and drier, long-term precipitation numbers may not change much. “If precipitation falls mostly during a few intense storms, then the flood flows could be quite large,” says Dusterhoff. “The best available science is telling us that large flood events will be getting larger, even with a drier future.”

Lotina Nishijima, project manager of McKelvey Park’s construction period for Valley Water, stresses the importance of winning over public support for a project of this scale. “I remember …hundreds of meetings and public workshops,” says Nishijima. “We don’t own the land along the creeks, so in order to get the right of way to build projects, working with cities and other entities is very important.”

McKelvey has been built, but others like it around the Bay Area have not been as successful. In Marin County, similar attempts to build a multipurpose detention-basin/baseball-park have foundered. Most recently, in 2017, a community-organized effort prevented plans of transforming Lefty Gomez Field, at Fairfax’s White Hill Middle School. The website saveleftygomez.com mentions drowning victims found in municipal flood-control facilities in Las Vegas and Pearl City, Hawaii, and expresses concerns over a potential attractive nuisance in the form of a standing body of water being located on middle-school grounds.

Warren Karlenzig, a Marin resident and president of sustainability consulting firm Common Current, whose work with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power helped it move to green infrastructure to reclaim stormwater, advocates for a more systemic approach to stormwater management. A flood protection plan “is not just a monolithic structure,” says Karlenzig. “Neighborhoods with rain gardens that channel rain from rooftops into areas that hold water, public works projects, volunteer projects,” all play a role.

The public works and volunteer projects that Karlenzig talks about have already demonstrated success in Marin County. On San Anselmo’s Red Hill Avenue, the Miracle Mile median project can hold one to two acre-feet of water, reducing the impact of localized flooding and droughts while cleaning pollutants from runoff. And at the Fairfax Pavilion, a parking lot badly eroded by poor stormwater drainage, Karlenzig organized a volunteer effort that, over the course of one weekend, constructed a bioretention system that held one million gallons of stormwater in its first year of use.

Karlenzig sees bioretention working in concert with larger engineering projects to help take some of the pressure off of structures like McKelvey Park. His systemic view is echoed by Rouhani of Valley Water, who talks about how detention basins take a watershed view of flood control. “You have to do things where it makes sense,” he says, “even if the project impact is in a different place than project benefits.”

The neighborhood around McKelvey Park has new baseball fields, and the neighborhoods downstream have flood protection without building unsightly flood walls along the creek channel. It seems like a win-win, but, when looking at the new facility, it’s easier to empathize with the skeptical residents. There’s something severe about the 18-foot concrete walls, and the tall iron fence along the sidewalk where there were once redwood trees. All too often, when it comes to planning for climate change, universally welcomed workable solutions don’t exist.

“I would say that a flood detention basin is the best tool for situations like Permanente Creek,” says Dusterhoff. “You don’t have a lot of options, like turning a floodplain back into a floodplain.” Since its completion, McKelvey Park has been well received, even winning several design awards, and Nishijima believes the praise is well earned. “We learned a lot and there were a lot of challenges,” she says. “It’s hard to make everybody happy.”

Top Photo: McKelvey Park by Michael Adamson

Prior Estuary News Stories

San Francisco Prepares for Water from All Directions, June 2020

LA Drainage Goes Native, June 2017

The Most Under-Regulated Facility, December 2015

Other Links