![]() Download: Estuary News, April 2013 PDF

Download: Estuary News, April 2013 PDF

Ideas for monumental scale interventions have started cropping up on the desks and drawing boards of Bay Area planners faced with the prospect of sea level rise. “We’re hearing about tidal barriers at the Golden Gate, and bigger and bigger levees, but then what happens to our marshes and mudflats?” says engineer Bob Battalio of the consulting firm ESA PWA. The answer, according to a new model developed by Battalio and colleague Jeremy Lowe — with the help of coastal ecologist Peter Baye, the Ora Loma Sanitary District’s Jason Warner, and East Bay Dischargers’ Mike Connor — is to integrate flood control with habitat restoration in a way that could bring back a lost ecosystem and streamline wastewater treatment, at a significant cost saving over traditional approaches. A recent report by The Bay Institute calls this concept the “horizontal levee.”

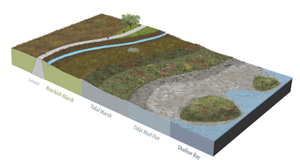

The term was borrowed from the Netherlands, but that’s the only resemblance to Dutch flood control practice. “They use large levees with asphalt and turf grass,” Battalio explains. “We emphasize natural shoreline formations and ecological function.” What’s being proposed is a gently sloping rise from the salt marsh along the Bay up into a wet marshy meadow in front of the levee (see diagram). Depending on lots of variables, the wet area on the landward transitional edge can be a “freshwater meadow,” “back marsh,” “brackish marsh,” or for purists, “estuarine terrestrial ecotone.”

The tidal marsh slows wave action and prevents levee overtopping in a flood or storm surge, while the upper marshy area gains elevation. Plant species adapted to fresh or brackish water grow faster and put down more roots than salt marsh species. By bulking up faster, and tolerating thin sediment deposits, the transitional marsh can keep pace with sea level rise longer.

“The concept is pretty simple: it’s a big, extra-wide, wet levee, runny (seeping) and supporting wetland vegetation on the slope instead of artificially dry upland vegetation.” says Peter Baye.

What’s missing for the Bay scenario is enough sediment and a source of fresh water to the transitional marsh, which was once fed by natural runoff. And that’s where the wastewater from Ora Loma, and material dredged out of flood control channels, comes in.

“The really new thing here is the idea of using treated wastewater to facilitate a brackish transition marsh farther upslope,” says Battalio. Treated wastewater may contain nutrients, which act like fertilizer. “Slope marshes with high nutrients are like wet prairies — very productive, depositing stable belowground biomass in soil that sequesters carbon and nutrients,” says Baye.

The proof of the concept may come at the Hayward shoreline. As Lowe explains it, a city council member persuaded the Hayward Area Shoreline Planning Area to commission a study of the shoreline’s future from ESA PWA. That led to the design of a demonstration project and The Bay Institute report. Lowe says Ora Loma Sanitary is interested because of the water quality benefits and potential reduction in operations costs. According to The Bay Institute’s Marc Holmes, the S.F. Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board also seems favorably inclined. He’d like to expand the scope to include other parts of the South Bay. But what may make the demo work in Hayward is a combination of forward-looking leadership and an effective local governance structure. Holmes hopes other cities will buy in, building a legislative campaign.

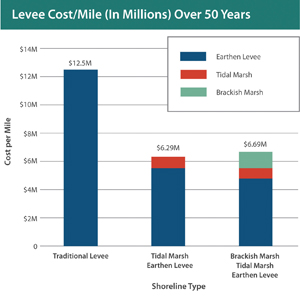

As for cost, Holmes says he was surprised by the difference between the horizontal levee and a more traditional 13-foot-high mound of dirt: “We did not anticipate the scale of the savings.” The study suggests that a traditional levee without a marsh would cost more than $12 million per mile over 50 years. With a 200-foot-wide salt marsh on the Bay, and/or a brackish marsh on the upland side of the levee, the price almost halves (see graph).

To Lowe and Battalio, using natural topography and native vegetation to knock down waves is not a radical departure. Others have floated the idea in the recent past. “Using the natural environment as much as possible is the kernel of our practice,” says Battalio. “We need to recognize the value of mudflats and marshes, and consider where we draw the line. Otherwise we might wind up spending more money and being less effective.”

Contact: Bob Battalio, [email protected]; Marc Holmes, [email protected]; Jeremy Lowe, [email protected]

By Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Nothing could be stranger than sitting in the dark with thousands of suits and heels, watching a parade of promises to decarbonize from companies and countries large and small, reeling from the beauties of big screen rainforests and indigenous necklaces, and getting all choked up.

It was day two of the September 2018 Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco when I felt it.

At first I wondered if I was simply starstruck. Most of us labor away trying to fix one small corner of the planet or another without seeing the likes of Harrison Ford, Al Gore, Michael Bloomberg, Van Jones, Jerry Brown – or the ministers or mayors of dozens of cities and countries – in person, on stage and at times angry enough to spit. And between these luminaries a steady stream of CEOs, corporate sustainability officers, and pension fund managers promising percentages of renewables and profits in their portfolios dedicated to the climate cause by 2020-2050.

I tried to give every speaker my full attention: the young man of Vuntut Gwichin heritage from the edge of the Yukon’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge who pleaded with us not to enter his sacred lands with our drills and dependencies; all the women – swathed in bright patterns and head-scarfs – who kept punching their hearts. “My uncle in Uganda would take 129 years to emit the same amount of carbon as an American would in one year,” said Oxfam’s Winnie Byanyima.

“Our janitors are shutting off the lights you leave on,” said Aida Cardenas, speaking about the frontline workers she trains, mostly immigrants, who are excited to be part of climate change solutions in their new country.

The men on the stage, strutting about in feathers and pinstripes, spoke of hopes and dreams, money and power. “The notion that you can either do good or do well is a myth we have to collectively bust,” said New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy whose state is investing heavily in offshore wind farms.

“Climate change isn’t just about risks, it’s about opportunities,” said Blackrock sustainable investment manager Brian Deese.

But it wasn’t all these fine speeches that started the butterflies. Halfway through the second day of testimonials, it was a slight white-haired woman wrapped in an azure pashmina that pricked my tears. One minute she was on the silver screen with Alec Baldwin and the next she taking a seat on stage. She talked about trees. How trees can solve 30% of our carbon reduction problem. How we have to stop whacking them back in the Amazon and start planting them everywhere else. I couldn’t help thinking of Dr. Seuss and his truffala trees. Jane Goodall, over 80, is as fierce as my Lorax. Or my daughter’s Avatar.

Analyzing my take home feeling from the event I realized it wasn’t the usual fear – killer storms, tidal waves, no food for my kids to eat on a half-baked planet – nor a newfound sense of hope – I’ve always thought nature will get along just fine without us. What I felt was relief. People were actually doing something. Doing a lot. And there was so much more we could do.

As we all pumped fists in the dark, as the presentations went on and on and on because so many people and businesses and countries wanted to STEP UP, I realized how swayed I had let myself be by the doomsday news mill.

“We must be like the river, “ said a boy from Bangladesh named Risalat Khan, who had noticed our Sierra watersheds from the plane. “We must cut through the mountain of obstacles. Let’s be the river!”

Or as Harrison Ford less poetically put it: “Let’s turn off our phones and roll up our sleeves and kick this monster’s ass.”

by Isaac Pearlman

Since California’s last state-led climate change assessment in 2012, the Golden State has experienced a litany of natural disasters. This includes four years of severe drought from 2012 to 2016, an almost non-existent Sierra Nevada snowpack in 2014-2015 costing $2.1 billion in economic losses, widespread Bay Area flooding from winter 2017 storms, and extremely large and damaging wildfires culminating with this year’s Mendocino Complex fire achieving the dubious distinction of the largest in state history. California’s most recent climate assessment, released August 27th, predicts that for the state and the Bay Area, we can expect even more in the future.

The California state government first began assessing climate impacts formally in 2006, due to an executive order by Governor Schwarzenegger. California’s latest iteration and its fourth overall, includes a dizzying array of 44 technical reports; three topical studies on climate justice, tribal and indigenous communities, and the coast and ocean; as well as nine region-specific analyses.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

For the first time, California’s latest assessment dives into climate consequences on a regional level. Academics representing nine California regions spearheaded research and summarized the best available science on the variable heat, rain, flooding and extreme event consequences for their areas. For example, the highest local rate of sea level rise in the state is at the rapidly subsiding Humboldt Bay. In San Diego county, the most biodiverse in all of California, preserving its many fragile and endangered species is an urgent priority. Francesca Hopkins from UC Riverside found that the highest rate of childhood asthma in the state isn’t an urban smog-filled city but in the Imperial Valley, where toxic dust from Salton Sea disaster chokes communities – and will only become worse as higher temperatures and less water due to climate change dry and brittle the area.

According to the Bay Area Regional Report, since 1950 the Bay Area has already increased in temperature by 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit and local sea level is eight inches higher than it was one hundred years ago. Future climate will render the Bay Area less suitable for our evergreen redwood and fir forests, and more favorable for tolerant chaparral shrub land. The region’s seven million people and $750 billion economy (almost one-third of California’s total) is predicted to be increasingly beset by more “boom and bust” irregular wet and very dry years, punctuated by increasingly intense and damaging storms.

Unsurprisingly, according to the report the Bay Area’s intensifying housing and equity problems have a multiplier affect with climate change. As Bay Area housing spreads further north, south, and inland the result is higher transportation and energy needs for those with the fewest resources available to afford them; and acute disparity in climate vulnerability across Bay Area communities and populations.

“All Californians will likely endure more illness and be at greater risk of early death because of climate change,” bluntly states the statewide summary brochure for California’s climate assessment. “[However] vulnerable populations that already experience the greatest adverse health impacts will be disproportionately affected.”

“We’re much better at being reactive to a disaster than planning ahead,” said UC Berkeley professor and contributing author David Ackerly at a California Adaptation Forum panel in Sacramento on August 27th. “And it is vulnerable communities that suffer from those disasters. How much human suffering has to happen before it triggers the next round of activity?”

The assessment’s data is publicly available online at “Cal-adapt,” where Californians can explore projected impacts for their neighborhoods, towns, and regions.