At a glance, the recent winter storms and inches of snow in the Sierra seem like a reassuring sign: more snow means more snow melt, which means more water moving through our freshwater systems during dry summer months.

But it turns out that there are different types of snow with differing levels of moisture locked up inside — and the latest Sierra snowfall appears to be holding less water than usual. This means the Bay’s streams and estuaries could have drier conditions ahead, despite this winter’s semi-regular storms.

Typically, snow that falls along the Sierra has a high moisture content because of the mountain range’s proximity to the Pacific Ocean, says Dan McEvoy, a regional climatologist with the Western Regional Climate Center in Reno, Nevada. But when storms instead originate in the north and travel over land before hitting the Sierra, a snowflake with more air and less moisture falls.

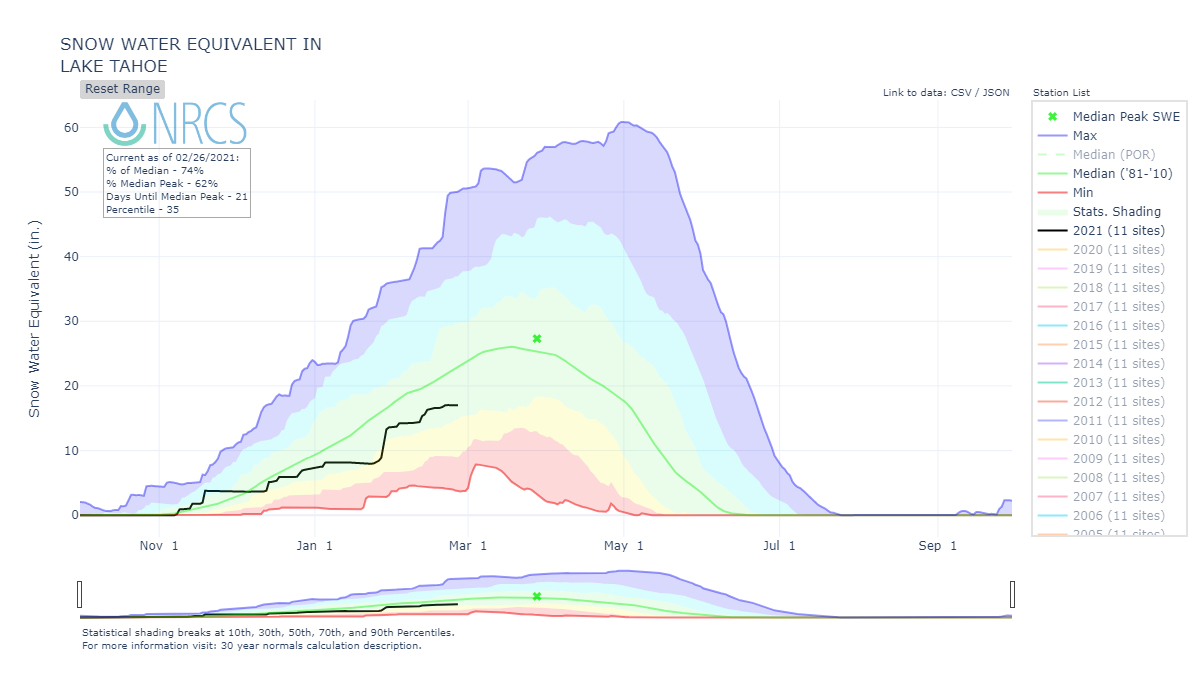

To quantify the amount of water in snow, researchers calculate the “snow water equivalent,” or SWE. “Right now, the entire Sierra is below average for SWE,” says McEvoy. Currently, snow in the central Sierra region, from Lake Tahoe to Bridgeport, has about 65 to 75% of its SWE, while the southern Sierra snow holds only 40 to 50% of the moisture compared to historical snow records.

According to McEvoy, it is possible for the water equivalent in Sierra snow to rebound this season, “but the odds are favoring below normal.” We’ll need to see multiple, significant snow storms delivering water-dense flakes in the next month or so to get the slow-release water that’s necessary to sustain normalcy in our estuaries and wetlands.

In general, snow is seen as such a valuable resource in California because it acts as a natural reservoir for water: as temperatures warm throughout the year, water is released little by little. Less water available in the snow that’s currently falling in the mountains means less water for all of the systems downhill later this year.

“Less water stored as snow in the Sierra may ultimately mean less water for Bay Area wetlands,” says Bea Gordon, a PhD researcher at the University of Nevada, Reno’s Hydrologic Sciences department. “If water supplies are reduced, difficult decisions will have to be made about where water goes, particularly when it comes to the environment.”

California’s freshwater is tightly regulated. From snow in the Sierra to water flowing through the Sacramento River into smaller estuaries, water-infrastructure systems built in the 20th century control where nearly every drop of water flows. But as our climate changes and weather patterns shift, more and more pressure is being placed on our water systems.

“As we get less snow, less melt, and less water, nothing downstream is changing: the people are still there,” says Newsha Ajami, director of urban water policy at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment. “One side of the equation is changing but not the other.”

According to Ajami, much progress has been made in managing the Bay Area’s freshwater as one, collective system. “The Bay is in a much better place than it was 20 to 30 years ago, but now the focus needs to be on climate-change impacts and how they are altering the Bay’s fragile equilibrium.”

Other contributors to that equilibrium are water conservation and recycling programs, activities that Northern California has undertaken with much less vigor than its southern counterpart, at least until drought became more persistent.

Local organizations including the East Bay Municipal Utilities District (EBMUD) are looking at a wide array of future weather scenarios to outline what needs to happen for freshwater to continue flowing to all of the Bay Area. Recent progress for the district includes setting water-use targets for urban suppliers, increasing adoption of recycled water, and focusing on groundwater conservation. (With an eye on the future, the district also recently approved a plan to become carbon-neutral for their water operations by 2030).

“Climate change is a growing threat to our planet and community,” says Jolene Bertetto, EBMUD Water Conservation Representative. “It’s really about making water conservation a way of life in a state that is drought-prone.”