Marsh restoration, Bay and Ridge Trail extensions, and urban park upgrades are among the types of projects eligible to receive funding through the 2019 Bay Area Priority Conservation Area (PCA) One Bay Area Grant Program. By March, aided by new mapping tools that can pinpoint regional landscape characteristics and needs, more than 36 cities, counties, agencies and non-profits had submitted letters of interest to the program, outlining a variety of projects that benefit one or more of the Bay Area’s 165 PCAs (see map opposite). Altogether, the grant requests totaled more than $19 million.

Some of these projects may help vulnerable shoreline areas defend against sea level rise; others may make urban hardscapes more porous under atmospheric river downpours; still others may connect vital migratory corridors for urban wildlife through the skyscrapers, industry, and neighborhoods of the metropolitan Bay Area.

“With this new stream of funding, you could say we have a goal of both growing and conserving the region at the same time,” says Matt Gerhart of the State Coastal Conservancy (SCC), which is managing the grants.

Important elements of the Plan Bay Area 2040, the current integrated long-range transportation and land-use plan for the region, PCAs are intended to complement areas designated for high-density growth, or Priority Development Areas. “Compared to other Bay Area natural lands, parks and preserves, the PCA network contributes a disproportionately high number of some ecosystem services,” says Heather Dennis of the SF Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s Adapting to Rising Tides (ART) project.

PCAs, which are nominated by local governments, agencies or non-profits, fall into four categories: natural landscapes, agricultural land, regional recreation and urban greening. Some PCAs fit more than one category, such as agricultural land that also provides recreational opportunities.

The first list of PCAs was assembled in 2008, when ABAG asked local interests and agencies around the Bay to suggest unprotected places where pastures, forests, vacant lots, creeks, and shorelines should be identified as a conservation priority. “Cities pushed back on that approach, because anyone was allowed to submit an idea, and they felt there was not enough consideration of existing municipal plans and priorities,” says Laura Thompson, Assistant Planning Director for the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG/MTC).

In the second round, cities were placed in the drivers seat—as primary nominators of PCAs—and they were also required to notify property owners of designations. A new category for PCAs of “urban greening” was also added. “ The urban greening category is important, because it creates opportunities for multi-benefit stormwater management practices, like rain gardens, and active transportation improvements, such as bike and pedestrian trails along greenway corridors,” says the San Francisco Estuary Partnership’s John Bradt. “These projects promote public awareness of resource protection, and public access to nature within built environment.”

In terms of the money to support these PCAs, the first round of PCA grants funded 23 projects around the Bay in 2013, ranging from recreational improvements to Mill Valley’s Bayfront Park to the purchase of 174 acres adjacent to San Mateo County’s Memorial Park for open space and recreation. Funds awarded totaled $12 million. In the second round, now underway, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) and the Coastal Conservancy have set aside $10 million for projects in the Peninsula, Southern and East Bay counties (the North Bay program is managed separately by local transportation agencies; in the second round of those grants, 11 projects were awarded a total of $8.2 million).

Projects eligible for funding during the current grant round must consist of at least one of five activities, within or adjacent to, a PCA: protection or enhancement of nature resources, open space or agricultural lands; pedestrian and bicycle facilities, urban greening; planning activities; and visual enhancements. After reviewing the letters of interest, regional agencies will invite selected projects to submit a full proposal by July.

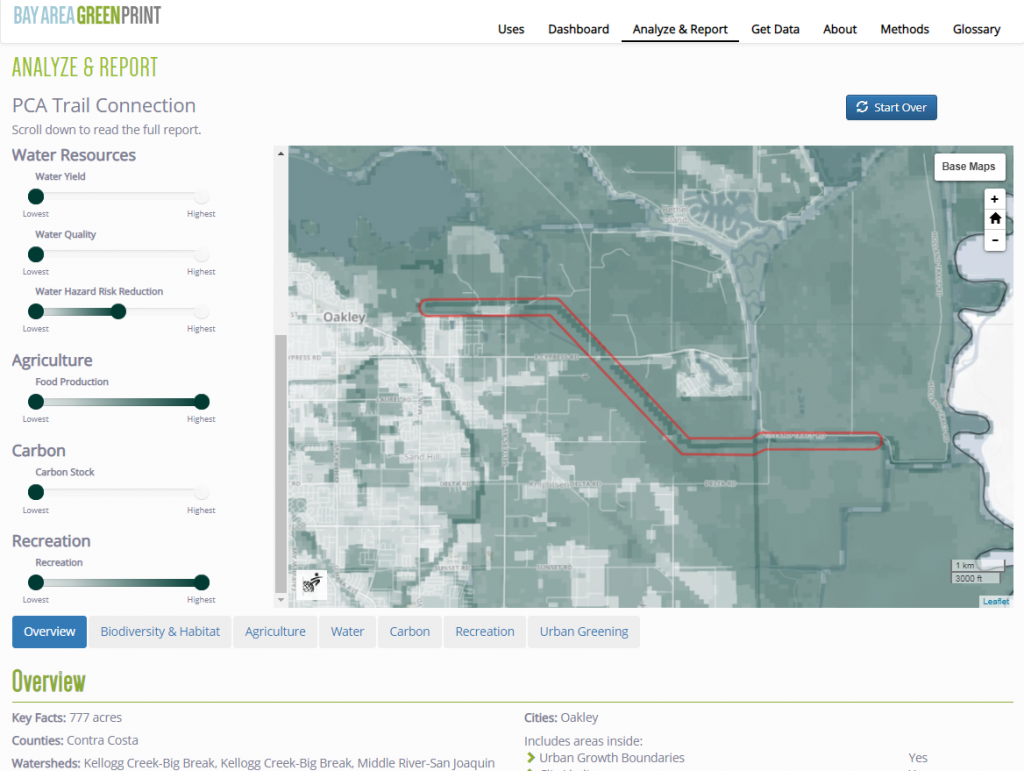

As part of the application process, PCA grant applicants must submit a project report through Bay Area Greenprint. This mapping and data tool was developed by the Greenbelt Alliance, the Nature Conservancy, the Bay Area Open Space Council, the American Farmland Trust and the Green Info Network. A Greenprint report identifies, maps and measures ecosystem values, and allows users to visually display and share a range of data about their project location—everything from its status as habitat for protected species to agricultural and recreational uses to carbon sequestering potential.

“The Greenprint allows you to see where within a PCA are the conservation priorities,” says Adam Garcia of Greenbelt Alliance, who gave a quick onscreen lesson in how to navigate the tool’s colorful and attractive menus at several recent workshops for grant applicants. “It can offer a snapshot of what’s in your project area right now and a way to assess multiple benefits, but it’s not a scenario planning tool.”

“The Greenprint helps us identify the highest priorities for conservation, based on values that we have all agreed on,” says Tom Robinson of the Bay Area Open Space Council. “No matter who is evaluating the projects, [we now have] a standard way to view them.”

Given the investment in PCA projects, figuring out how to protect them from the effects of climate change, and leverage them to protect other assets, is a priority. With funding from MTC, BCDC’s ART Bay Area program conducted vulnerability assessments of 19 PCAs around the Bay in 2018. Among the findings was that more than 50 percent of the recreation that the PCA network provides, and all of the PCAs that are critical for coastal protection, are vulnerable to sea level rise and flooding. Findings also compared ecosystem services provided by PCAs across the region using ecosystem valuation models developed by the Natural Capital Project, a collaboration between Stanford University, University of Minnesota, the World Wildlife Fund, and the Nature Conservancy.

“We are hoping that this analysis will help guide where future PCAs make sense, and also how projects within existing PCAs might speak to the vulnerabilities that we’ve identified,” says BCDC’s Dennis. For example, the PCA around Oakland’s Damon Slough has wetlands that may provide flood protection to the Coliseum area PDA, as well as nearby transportation infrastructure. Next, ART will examine issues such as what adaptation strategies might make PCAs more resilient, and whether rising sea levels warrant changes in how PCAs are designated and funded.

“The ART analysis isn’t intended to dictate how the PCA program operates, or whether there should be a change in our regional approach to natural lands, “ says the ART program’s new director Dana Brechwald. “That’s a bigger conversation. This analysis could help us think about a regional approach in new ways.”

The PCA program has evolved to more effectively balance Bay Area-wide priorities, says The Nature Conservancy’s Liz O’Donoghue. “There will always be tension between locally identified, locally driven priorities, which is really how on-the-ground conservation is most successful, and the need for local conservation priorities and projects to support and be driven by regional priorities, so you can get to landscape-scale conservation.”

“We’re not there yet, in terms of adding another layer of regional analysis to the locally-driven PCA designation process, but we will be taking a new look at the PCA-PDA balance next year through MTC’s Horizons and scenario development program. Staff are still discussing all this internally, but given all the pressures in the region for growth, climate adaptation, and ecosystem services, being more strategic could pay off,” says ABAG/MTC’s Thompson.

Whether and where additional PCAs will be designated are questions to be answered in Plan Bay Area 2050, which is slated to be released in 2021. “In the months ahead we will be working to update our growth framework, which might include an opportunity for new PCAs to be submitted and considered,” says MTC’s Dave Vautin. “We’ve been working closely with the ART Bay Area team over the last year as we start preparing for PBA2050,” he says.

The Nature Conservancy’s O’Donoghue is bullish on the future of the PCA program. “It supports the Bay Area’s vision for growth and reflects the importance of conservation in the area, as well as MTC’s and SCC’s innovation in figuring out how the local and regional connect and support each other. I think its just getting better and better.”

Note: Caption information reported by Joe Eaton.

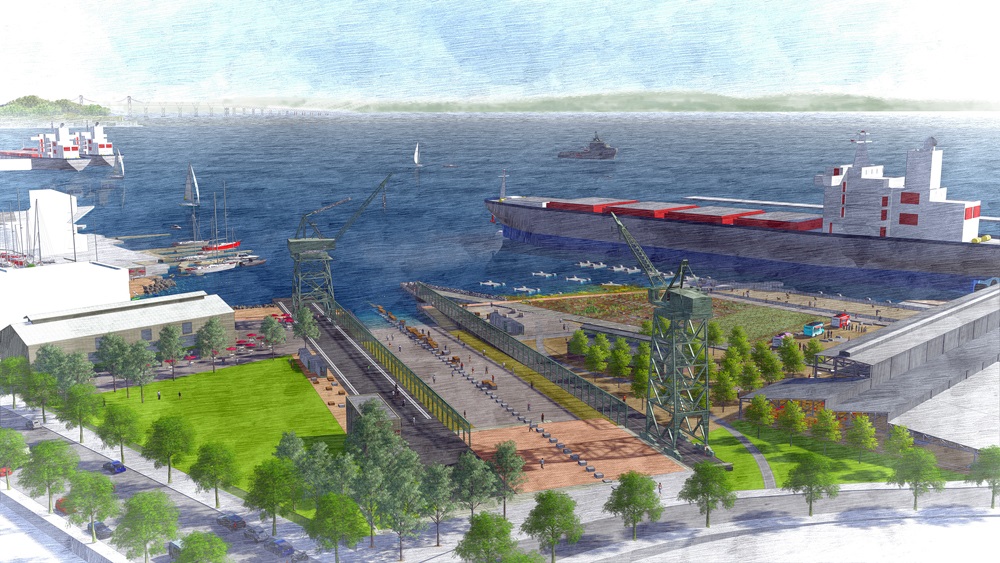

Top photo: Albany beach restoration and construction of the new PCA project and Bay Trail link. Photo: Ron Sullivan