“Without data, we wouldn’t have much to say about the State of the Estuary,” said James Cloern, as he kicked off the second session of Wednesday’s morning plenaries on water quality. After thirty years of watching the ups and downs in the data streams coming in from various monitors in the Estuary, this US Geological Survey senior scientist is an avid proponent of public investment in collecting data on the water, in the water, over decades, and on a regular basis. His newest conclusion, after reviewing the latest trends in phytoplankton biomass and suspended sediment concentrations, is that the Bay’s historic resistance to nutrient pollution is weakening.

“Without data, we wouldn’t have much to say about the State of the Estuary,” said James Cloern, as he kicked off the second session of Wednesday’s morning plenaries on water quality. After thirty years of watching the ups and downs in the data streams coming in from various monitors in the Estuary, this US Geological Survey senior scientist is an avid proponent of public investment in collecting data on the water, in the water, over decades, and on a regular basis. His newest conclusion, after reviewing the latest trends in phytoplankton biomass and suspended sediment concentrations, is that the Bay’s historic resistance to nutrient pollution is weakening.

“The Estuary’s resistance comes from strong tides, high turbidity, and fast grazing [of algal blooms] by clams, but I’ve seen four signs that the Bay could now be on a trajectory toward the kinds of impairments seen in other nutrient-rich estuaries,” said Cloern.

Cloern showed slides of “dead zones” in East Coast estuaries by way of example. He explained that many estuaries have been enriched with nutrients derived from fertilizer runoff, fossil fuel combustion, and sewage discharge. Nutrient enrichment promotes fast production of phytoplankton biomass, he said, and in places such as Long Island Sound and Chesapeake Bay the metabolism of that biomass depletes oxygen from water and creates dead zones devoid of fish and shellfish. Research shows that San Francisco Bay receives higher nutrient loads than these estuaries, primarily from river inputs to the North Bay and treated sewage in South Bay, yet it does not suffer from high phytoplankton biomass or low oxygen because it has attributes that give resistance.

Following the data record, however, Cloern detected the first signs of weakening resistance in the South Bay starting in 1999. He noted a decline in clam abundance, a red tide in 2004, the presence of new harmful species in the phytoplankton community, and a significant jump in phytoplankton biomass. Where blooms mainly used to occur only in spring, Cloern and his team have more recently been recording these events in summer and autumn, too. “These kinds of events always occur during heat waves with calm winds. Waters mix very slowly, leading to exceptional blooms, and sometimes to red tides,” he said, showing pictures of crimson algae clouding grey waters off the side of the USGS research vessel Polaris.

Despite the rise in blooms, and the presence of plankton species that can be toxic if consumed by clams and fish, Cloern said he’d seen no evidence of associated fish mortality in San Francisco Bay so far.

But alarm bells are ringing based on these kinds of observations. The San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board is now developing a nutrient strategy for the Bay in partnership with the Regional Monitoring Program, wastewater dischargers, and the scientific community. “Much is at stake because the capital costs of nutrient removal could be $5-10 billion,” said Cloern, referring to the increased levels of wastewater treatment and pollution prevention required to tackle the problem. Other factors planners may need to keep in mind in developing the strategy are the opening of large new areas of salt ponds to tidal action, some of which could be incubators of harmful species of phytoplankton. Changes in ocean conditions also should be considered. “San Francisco Bay is connected to the shelf waters outside the Golden Gate where upwelling occurs, so the ocean can be a source of phytoplankton coming into the Bay,” he said. “The Estuary is in a continual state of evolution, and there is great uncertainty about how the future will unfold,” Cloern concluded.

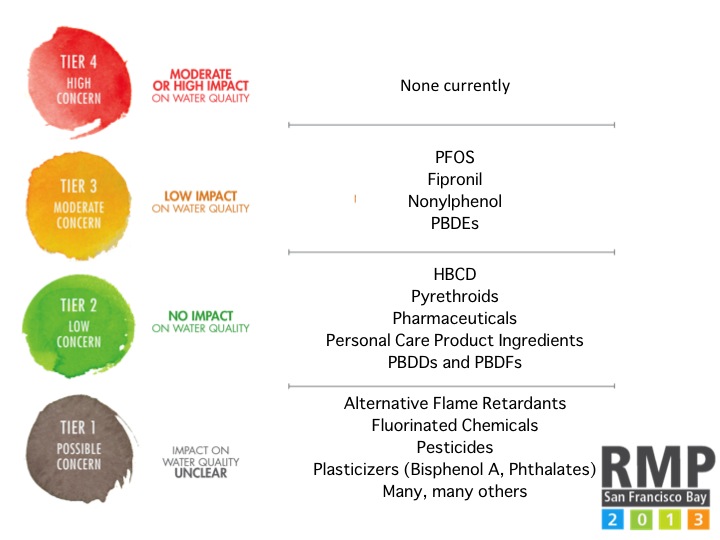

Nutrients aren’t the only unknown worrying those monitoring water quality and ecosystem health in the San Francisco Estuary. A whole suite of chemicals now being used in homes, businesses, industries and farms today aren’t yet even possible to detect, let alone plan for or prevent from entering the estuary. The next speaker, Derek Muir, came all the way from Environment Canada in Toronto to explain why.

Muir, a senior research scientist, defines these chemicals of emerging concern (CECs) as any synthetic chemical that is not regulated or commonly monitored in the environment but that also has the potential to enter the environment and cause adverse ecological or human health impacts. He commended San Francisco Bay’s Regional Monitoring Program for being one of the first on the continent to spotlight CECs, and guesstimated that globally there could be as many as 73 million known organic and inorganic substances, 19 million of which might actually be commercially available, 308,000 of which are inventoried and regulated, and only 500 of which might be routinely measured in environmental media (see slide).

“It’s misleading to think everything on the list of known chemicals is actually in commerce,” he said. For example, of the 73 million known chemicals on one list or another, only 30,000 are produced in quantities of more than one ton per year worldwide. The lists, and who compiles them, turn out to be important in getting a handle on the problem and prioritizing chemicals for more scrutiny. California and Oregon lead the world in making authoritative lists of safe or problematic chemicals.

Muir focused the rest of his talk on new tools for screening chemical safety. For example, a chemical’s potential for persistence, bioaccumulation, biodegradability, and adverse effects can be assessed based on its molecular structure using widely available quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs). “Our computer models tell our chemists what to look for in terms of molecular structure,” he said.

According to Muir, large lists of industrial organic chemicals, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals in Europe and the USA have already been screened and categorized by QSARs. These studies, as well as ongoing priority setting by chemical regulators in the US EPA, individual US states, Canada, the European Union, Japan and other countries suggest that about three percent of about 100,000 substances screened so far may be of concern.

“Not everything worth measuring is measurable; nor is everything measured worth measuring,” said Muir, quoting a US EPA maxim. “It’s easy to get off on tangents. But what we have now is a convergence of information which will help us rule out some chemicals.”

Like every good scientist, Muir couched his words with caveats, pointing out that most screening exercises do not include the possible degradation products, byproducts, and impurities of chemicals. He ticked off a number of other problems with current screening approaches, including the focus on registered chemicals. He also noted that many industrial chemicals may never be released into the environment, whereas many low volume personal care products like estrogen and antimicrobials, as well as pesticides, are regularly released into surface waters via wastewater or runoff.

The good news is that despite the challenges, there is a relatively large international effort to develop new tools for rapid screening of chemical toxicity, and to improve QSARs. “Screening can be successful if you have a tiered approach, good instrument technology, and good computer models,” said Muir. (See also afternoon Water Quality session on CECs).

The final speaker of the Wednesday plenary was Debbie Raphael, director of California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control. She radiated pep and purpose from the podium, as she announced a new tool in the water quality toolbox: California’s groundbreaking Safer Consumer Product Regulations, which went into effect in fall 2013. She also highlighted a new era of partnership, supported by Governor Jerry Brown, “who really pushes partnership,” she said. According to Raphael, many voices contributed to the final form of the regulations over the five years since the underlying law was enacted.

The regulations identify 1,200 chemicals known to be problematic for human health or the environment. Many of the chemicals are contaminants of concern for California’s water bodies, such as triclosan in personal care products, copper in marine paint, and coal tar in pavement sealants, to name just three. Using this list, the state Department of Toxic Substances Control is identifying specific “Priority Products” formulated using one or more of these chemicals, said Raphael. Manufacturers who wish to sell a “Priority Product” into California must either reformulate the product or justify the continued use of the chemical or chemicals of concern by submitting a robust Alternatives Analysis. “This is a powerful tool for public agencies and nonprofits trying to achieve source control of water contaminants,” said Raphael.

Raphael described the paradigm shift created by the alternatives analysis requirement and the mandate to avoid “regrettable substitutes,” where a banned substance is replaced with an equally harmful one. “This regulation shifts the focus. Instead of asking, ‘Is it legal to put this chemical in this carpet?,’ the new questions are ‘Is it safe? And is it necessary?’” The burden of proof is on the manufacturer. “Often the answer is ‘no,’ and often there are safer alternatives. We’re not telling them how to design their product, we’re just asking them to justify their design decisions,” says Raphael.

In general, the regulations are set up in a way that allows affected industries and communities of concern to continue to weigh in. They’re also designed so that water quality, and the health of California’s aquatic ecosystems, are priorities. Products on the market in California have to meet special requirements, just as cars have to be more efficient and less polluting in the Golden State, among other groundbreaking examples. “So it’s not about where it’s made, it’s about whether you want to sell it here,” says Raphael.

Raphael’s department plans to keep in close touch with water quality regulators about what chemicals or activities are giving them the most “heartburn.” She wants to ensure the two state programs intersect. “When we look at the Bay, we see its beauty and how much we enjoy it, but we also know there’s stuff in it we don’t want in it. This little safer consumer product regulation is really wanting to be at the table with you,” she said, looking out at the audience of engineers, scientists, resource managers and regulators.

Potential threats to the program on the horizon include resource limitations, lack of information on chemical hazards and exposure pathways, and pre-emption at the federal level. For the moment, however, there are signs that the marketplace is responding to the new initiative. Raphael recently saw an article on safer adhesives in Floor Covering Weekly, for example. “The world is watching,” she said.

San Jose Mercury News –Bay Getting Clearer

Safer Consumer Products

Chemicals of Emerging Concern in San Francisco Bay – Summary

[toggle_box]

[toggle_item title=”PowerPoint Gallery” active=”false”]

” color=”blue”]

Between plenaries, Friends of the San Francisco Estuary presented five awards for outstanding environmental projects in 2013. Recipients included California State Parks for the Yosemite Slough Restoration; the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture and other partners for the RMSAR designation of the Estuary as the 35th US wetland of international importance; the East Bay Regional Park District for their new Big Break Regional Shoreline interpretive center on the Delta, and their tidewater service area outreach project in East Oakland, educating local communities and school children; and the Western Recycled Water Coalition whose 22 member agencies and 25 projects recycle 120,000 acre feet of water annually.

Between plenaries, Friends of the San Francisco Estuary presented five awards for outstanding environmental projects in 2013. Recipients included California State Parks for the Yosemite Slough Restoration; the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture and other partners for the RMSAR designation of the Estuary as the 35th US wetland of international importance; the East Bay Regional Park District for their new Big Break Regional Shoreline interpretive center on the Delta, and their tidewater service area outreach project in East Oakland, educating local communities and school children; and the Western Recycled Water Coalition whose 22 member agencies and 25 projects recycle 120,000 acre feet of water annually.

Photo: SFEP[/message_box]

By Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Nothing could be stranger than sitting in the dark with thousands of suits and heels, watching a parade of promises to decarbonize from companies and countries large and small, reeling from the beauties of big screen rainforests and indigenous necklaces, and getting all choked up.

It was day two of the September 2018 Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco when I felt it.

At first I wondered if I was simply starstruck. Most of us labor away trying to fix one small corner of the planet or another without seeing the likes of Harrison Ford, Al Gore, Michael Bloomberg, Van Jones, Jerry Brown – or the ministers or mayors of dozens of cities and countries – in person, on stage and at times angry enough to spit. And between these luminaries a steady stream of CEOs, corporate sustainability officers, and pension fund managers promising percentages of renewables and profits in their portfolios dedicated to the climate cause by 2020-2050.

I tried to give every speaker my full attention: the young man of Vuntut Gwichin heritage from the edge of the Yukon’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge who pleaded with us not to enter his sacred lands with our drills and dependencies; all the women – swathed in bright patterns and head-scarfs – who kept punching their hearts. “My uncle in Uganda would take 129 years to emit the same amount of carbon as an American would in one year,” said Oxfam’s Winnie Byanyima.

“Our janitors are shutting off the lights you leave on,” said Aida Cardenas, speaking about the frontline workers she trains, mostly immigrants, who are excited to be part of climate change solutions in their new country.

The men on the stage, strutting about in feathers and pinstripes, spoke of hopes and dreams, money and power. “The notion that you can either do good or do well is a myth we have to collectively bust,” said New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy whose state is investing heavily in offshore wind farms.

“Climate change isn’t just about risks, it’s about opportunities,” said Blackrock sustainable investment manager Brian Deese.

But it wasn’t all these fine speeches that started the butterflies. Halfway through the second day of testimonials, it was a slight white-haired woman wrapped in an azure pashmina that pricked my tears. One minute she was on the silver screen with Alec Baldwin and the next she taking a seat on stage. She talked about trees. How trees can solve 30% of our carbon reduction problem. How we have to stop whacking them back in the Amazon and start planting them everywhere else. I couldn’t help thinking of Dr. Seuss and his truffala trees. Jane Goodall, over 80, is as fierce as my Lorax. Or my daughter’s Avatar.

Analyzing my take home feeling from the event I realized it wasn’t the usual fear – killer storms, tidal waves, no food for my kids to eat on a half-baked planet – nor a newfound sense of hope – I’ve always thought nature will get along just fine without us. What I felt was relief. People were actually doing something. Doing a lot. And there was so much more we could do.

As we all pumped fists in the dark, as the presentations went on and on and on because so many people and businesses and countries wanted to STEP UP, I realized how swayed I had let myself be by the doomsday news mill.

“We must be like the river, “ said a boy from Bangladesh named Risalat Khan, who had noticed our Sierra watersheds from the plane. “We must cut through the mountain of obstacles. Let’s be the river!”

Or as Harrison Ford less poetically put it: “Let’s turn off our phones and roll up our sleeves and kick this monster’s ass.”

by Isaac Pearlman

Since California’s last state-led climate change assessment in 2012, the Golden State has experienced a litany of natural disasters. This includes four years of severe drought from 2012 to 2016, an almost non-existent Sierra Nevada snowpack in 2014-2015 costing $2.1 billion in economic losses, widespread Bay Area flooding from winter 2017 storms, and extremely large and damaging wildfires culminating with this year’s Mendocino Complex fire achieving the dubious distinction of the largest in state history. California’s most recent climate assessment, released August 27th, predicts that for the state and the Bay Area, we can expect even more in the future.

The California state government first began assessing climate impacts formally in 2006, due to an executive order by Governor Schwarzenegger. California’s latest iteration and its fourth overall, includes a dizzying array of 44 technical reports; three topical studies on climate justice, tribal and indigenous communities, and the coast and ocean; as well as nine region-specific analyses.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

For the first time, California’s latest assessment dives into climate consequences on a regional level. Academics representing nine California regions spearheaded research and summarized the best available science on the variable heat, rain, flooding and extreme event consequences for their areas. For example, the highest local rate of sea level rise in the state is at the rapidly subsiding Humboldt Bay. In San Diego county, the most biodiverse in all of California, preserving its many fragile and endangered species is an urgent priority. Francesca Hopkins from UC Riverside found that the highest rate of childhood asthma in the state isn’t an urban smog-filled city but in the Imperial Valley, where toxic dust from Salton Sea disaster chokes communities – and will only become worse as higher temperatures and less water due to climate change dry and brittle the area.

According to the Bay Area Regional Report, since 1950 the Bay Area has already increased in temperature by 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit and local sea level is eight inches higher than it was one hundred years ago. Future climate will render the Bay Area less suitable for our evergreen redwood and fir forests, and more favorable for tolerant chaparral shrub land. The region’s seven million people and $750 billion economy (almost one-third of California’s total) is predicted to be increasingly beset by more “boom and bust” irregular wet and very dry years, punctuated by increasingly intense and damaging storms.

Unsurprisingly, according to the report the Bay Area’s intensifying housing and equity problems have a multiplier affect with climate change. As Bay Area housing spreads further north, south, and inland the result is higher transportation and energy needs for those with the fewest resources available to afford them; and acute disparity in climate vulnerability across Bay Area communities and populations.

“All Californians will likely endure more illness and be at greater risk of early death because of climate change,” bluntly states the statewide summary brochure for California’s climate assessment. “[However] vulnerable populations that already experience the greatest adverse health impacts will be disproportionately affected.”

“We’re much better at being reactive to a disaster than planning ahead,” said UC Berkeley professor and contributing author David Ackerly at a California Adaptation Forum panel in Sacramento on August 27th. “And it is vulnerable communities that suffer from those disasters. How much human suffering has to happen before it triggers the next round of activity?”

The assessment’s data is publicly available online at “Cal-adapt,” where Californians can explore projected impacts for their neighborhoods, towns, and regions.