by Joe Eaton

The numbers are daunting: 8,000 acres to be restored to fish-friendly tidal habitat in order to comply with federal wildlife agencies’ Biological Opinions; another 65,000 if and when the Bay-Delta Conservation Plan is implemented; more still if you add in mitigation for levee operations. Where will that acreage come from? State agencies and other public entities already

own some parcels suitable for restoration, but not nearly enough: the rest will need to be purchased from its current owners or covered by easements. (Eminent domain is not on the table; it’s not even clear if it could be invoked for habitat purposes.) And legal constraints make buying land in the Delta harder than you might think. Dennis McEwan of the Department of Water Resources Fish Restoration Program explains the process: “When there’s a property of interest, we have a separate state agency, the Department of General Services, do an appraisal. They come up with one, we communicate it to the owner, and it’s a matter of take it or leave it. We can’t negotiate a price with the landowner owing to state regulations.” Potential sellers often choose to leave it.

Land for restoration must be appraised at fair market value based on its current use — as cropland, pasture, a duck-hunting club in Suisun Marsh — rather than its potential for restoration. “Anything above fair market value is a gift of public funds,” McEwan adds. “The appraisal industry hasn’t caught up with the restoration industry,” notes DWR’s Gail Newton, of the department’s FloodSAFE Environmental Stewardship and Statewide Resources Office.

“If the value of the property is as a duck club, that’s not very much,” says Carl Wilcox of the Department of Fish and Wildlife, another major player in Delta restoration. “People aren’t standing in line to buy duck clubs. Someone who thinks they should be getting more has a tough time accepting that.” That limits options for DWR and DFW, the two largest players, both with new pots of money for restoration from Proposition 1. Land trusts and other nonprofits have a relatively limited role in Delta land acquisition. The Nature Conservancy is no longer actively seeking properties there, and other nonprofits have funding issues and liability concerns. The Delta Conservancy, a product of the 2009 Delta Reform Act, does not yet own or manage land, although that may change. Agencies looking for land have encountered the perception that the state already owns enough acreage to meet current restoration targets. But not all Delta land is equal.

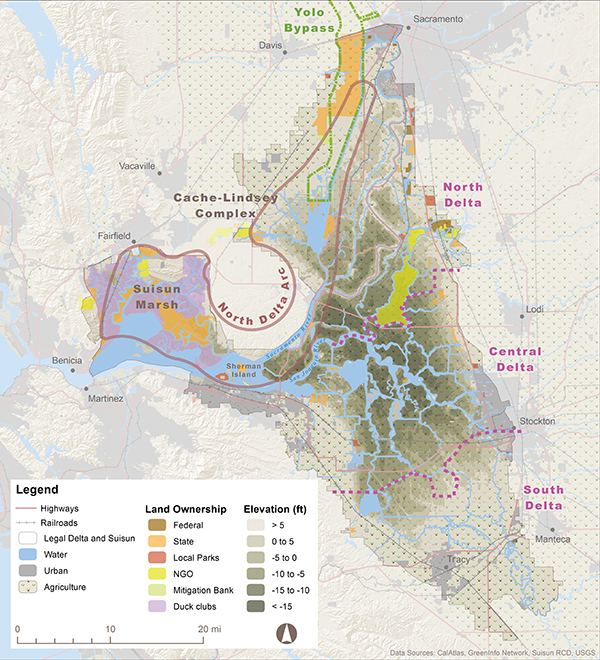

“People ask us why we don’t put the restoration on Sherman Island, since we own it,” says McEwan. “You’d get a fifteen-foot-deep lake, not tidally influenced marsh and subtidal habitat. It’s too subsided.” Wilcox concurs: “There’s quite a lot of publicly owned land that could be restored, but it would be expensive because of subsidence or the long-term processes involved.” Other complications include proximity to infrastructure (railroads, highways, gas wells) or flood liability concerns for adjacent properties. The state agencies are also focusing more on priority areas like the North Delta Arc, including Cache Slough and the Lower Sacramento River.

Land purchases by private mitigation banks like Westervelt and Wildlands may have complicated things by creating unrealistic expectations of what the state should pay. “Mitigation banks do recognize the restored value of the property,” says McEwan. “We can’t compete with them.” For agencies, buying mitigation credits from a bank could count toward restoration goals. With banks charging up to $60,000 per acre that would be another expensive proposition. Some sellers may have nonpecuniary issues. “We haven’t had anyone say, ‘We’d like to sell but we don’t like DWR because of the tunnels,’” McEwan comments. “We haven’t seen that.” The Delta Conservancy’s Campbell Ingram sees distrust of state-agency intentions as a factor, though, at least in some parts of the Delta: “If you as a landowner opted to sell land for restoration, you might not be viewed favorably within that community.” Such resistance is a particular issue in the South Delta, with “more larger-scale agriculture and more disbelief that it ever was tidal habitat.” Suisun Marsh, not part of the statutory Delta but included with it for some planning purposes, is a special case.

Seventy-five percent of the marsh is privately-owned, and duck clubs, some with a century of history, account for almost all of the that. There’s been speculation for years that club owners, with aging memberships and high maintenance costs, would be anxious to sell. Some clubs are in fact on the market, and one that recently changed hands is being restored by the State and Federal Contractors Water Agency. There’s no wholesale turnover, though. “I don’t see the decline,” says Steve Chappell of the Suisun Resource Conservation District. And owners might not even be attracted by higher prices: “They’re tied to the land, invested in these properties. It’s not like selling a tract home in the suburbs. Some were their grandfathers’ property, and they cherish these places,”says Chappell. Also, duck club properties are already being managed for wildlife; conversion to tidal wetland would be a change in habitat type, with concomitant winners and losers. Where price is the sticking point, can anything be done to give the agencies more leverage?

“It’s a matter of working with the agencies to bring the value up significantly higher than agricultural value, while making sure it doesn’t get out of hand and become a snowballing speculative free-for-all,” says Ingram. “We’re elevating the issue within our department, trying to come up with a potential solution,” McEwan adds. “We think there might be some tools out there.” Wilcox sees hope in market forces: “As time goes by and a market develops, there may be something that changes the comparable to where a little more can be paid.” Other sources of resistance may be amenable to dialogue and time. As a participant in the Delta Dialogues sponsored by Ingram’s Conservancy to bring agency representatives and in-Delta community leaders together, Wilcox sees value in inclusive collaboration — and patience: “People in the Yolo Bypass get it and understand what’s going on whereas in a lot of other places restoration is not really understood and viewed as

threatening. Dialogue is not something that happens quickly. It requires a lot of engagement over a long period of time. People have been talking in the Bypass for 15 or 20 years, and we’re finally getting to the stage where there’s a lot of interest in multi-pronged projects that address flood issues in conjunction with providing fisheries enhancements and improved drainage for agriculture, all in one package.” That, he suggests, might be what’s needed in places like the South Delta.

RELATED LINKS:

Delta Conservancy Report

NEXT ARTICLE: Beyond the Bag Ban